Panorama

- Norden’s Panorama

- Baker’s London Panorama

- Girtin’s panorama

- Girtin’s panorama - Animations

- Etching after Girtin’s panorama

- Contemporaries

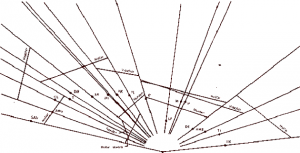

Norden’s Panorama

- Norden’s Panorama (1600-15)

- Vischer and Hollar panoramas, by John Orrell, The Quest for Shakespeare’s Globe

(Cambridge University Press,1983)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the late eighteenth century, visual effects are the reverse of the framed view of earlier times, which evolved under the influence of companion pictures and wide angle vision towards greater breadth of field; the central axis tends to vanish.

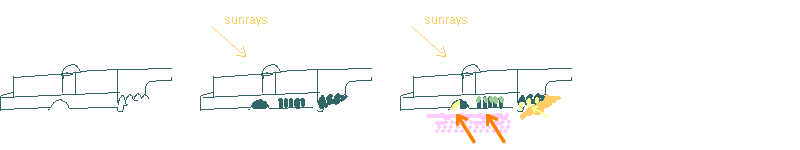

- Construction diagram of the Norden

- Vischer and Hollar panoramas, by John Orrell, The Quest for Shakespeare’s Globe

(Cambridge University Press,1983)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The basis is that of panoramic views of London from Southwark by seventeenth-century cartographers such as Norden: a sequence of views done by an observer turning on himself, producing a polygon assimilated to a circle.

Baker’s London Panorama

- interior cross-section of the panorama (early 19th c.) and view of the remaining rotunda (nowadays the church of Notre-Dame de France, Leicester Place)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Barker opened a panorama in Leicester Fields in the last years of the eighteenth century.

The views are placed on the inner walls of a circular room in which the visitors look in all directions successively.

- Baker’s London Panorama

- Plan, with English and French wording, of Baker’s London Panorama, from a Continental guide to the Panorama (B.M. Dept. of Prints and Drawings)

“the subject at present of the panorama painted by R. Barker, Patentee for the invention, is a view at a glance of the Cities of London and Westminster, comprehending the three bridges, represented in one painting, containing 1479 square feet, which appears as large and in every respect the same as reality”

“The Painting of the panorama of london and westminster will be lighted up with lamps which have a beautiful effect”

(January 1793)

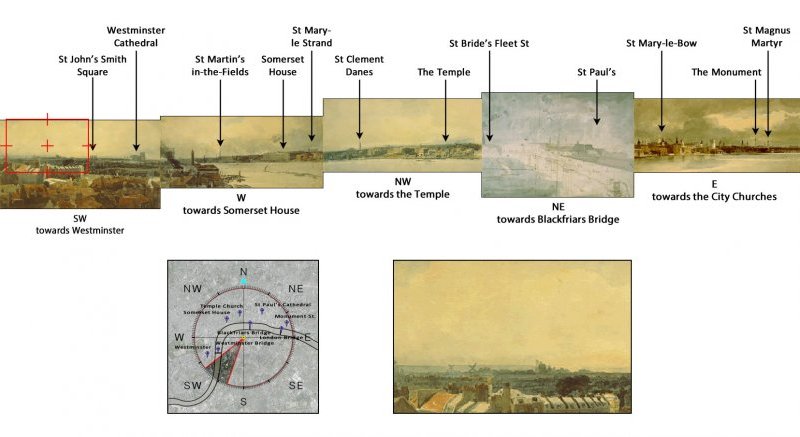

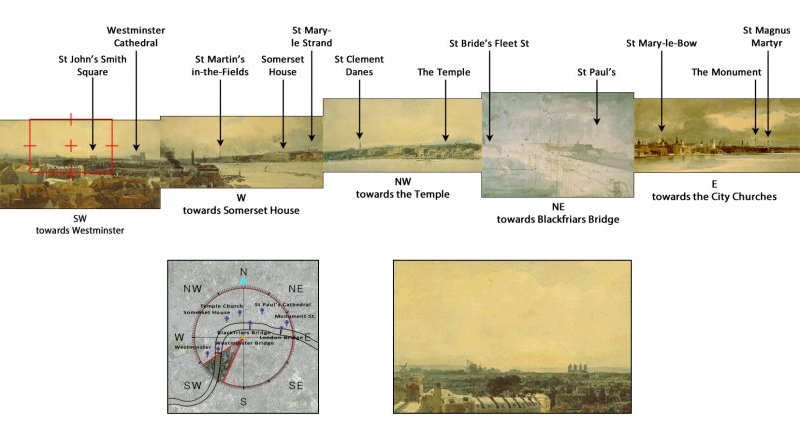

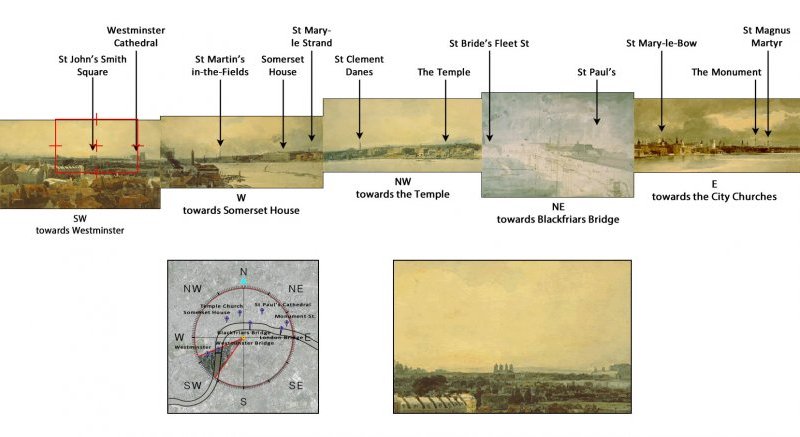

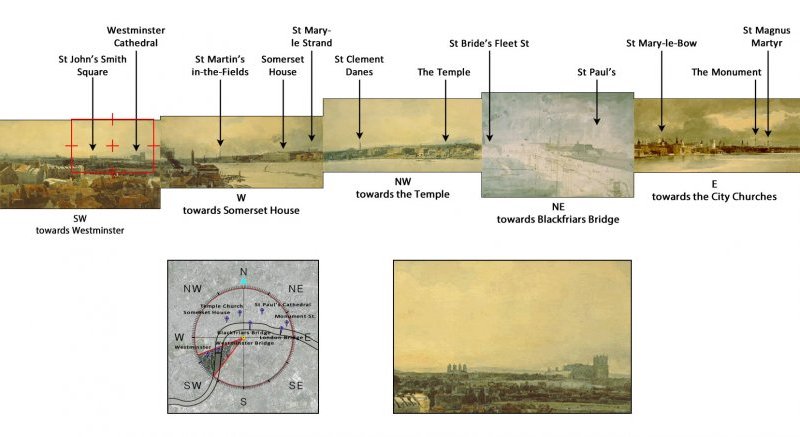

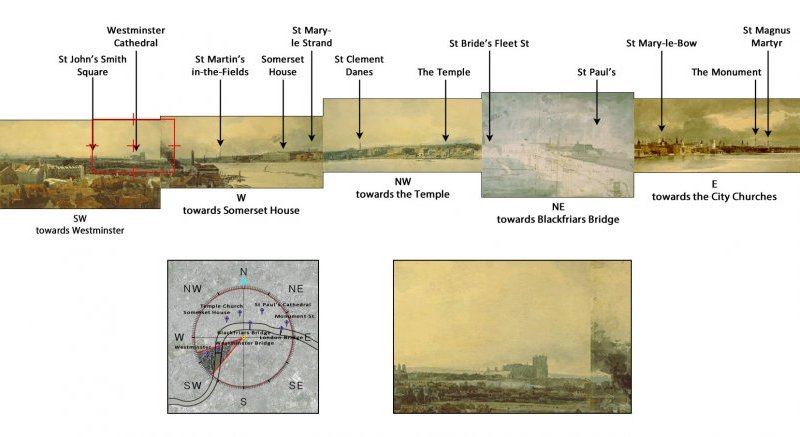

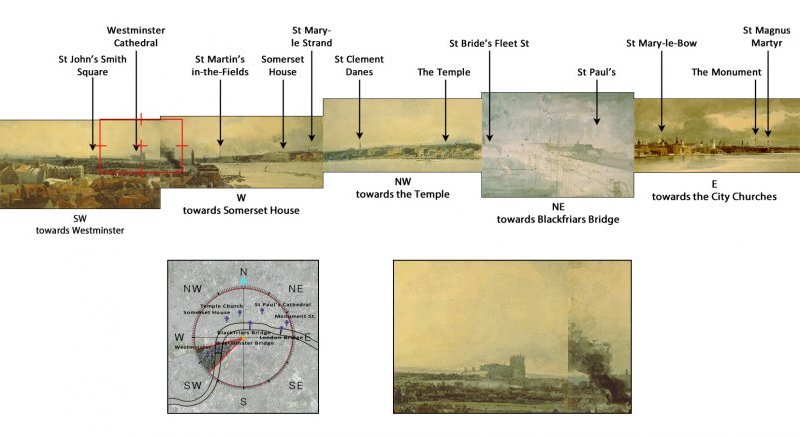

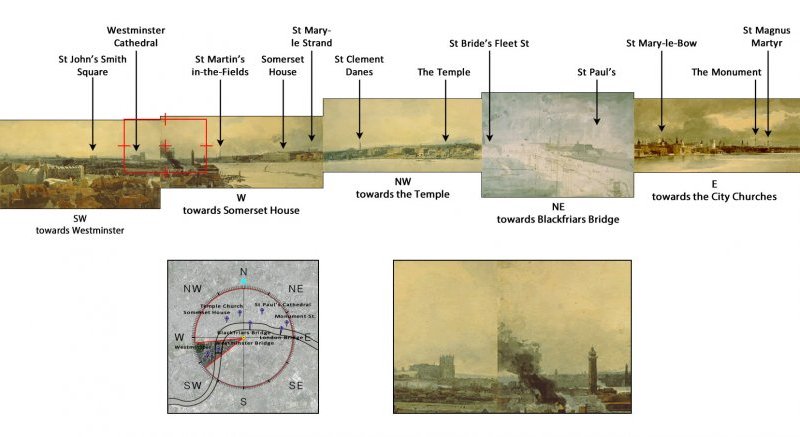

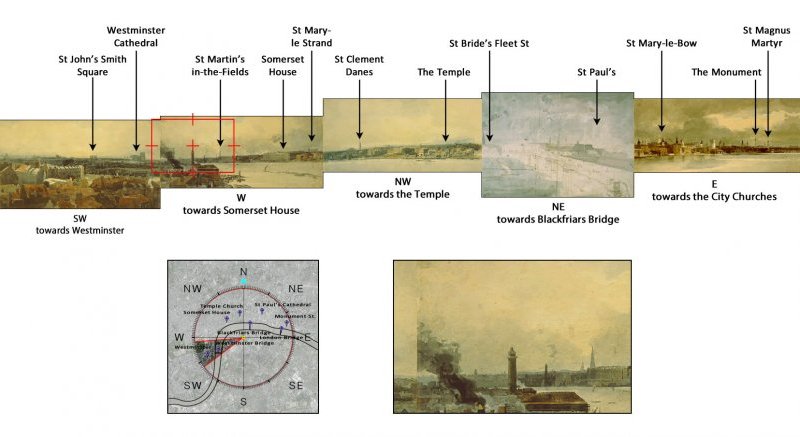

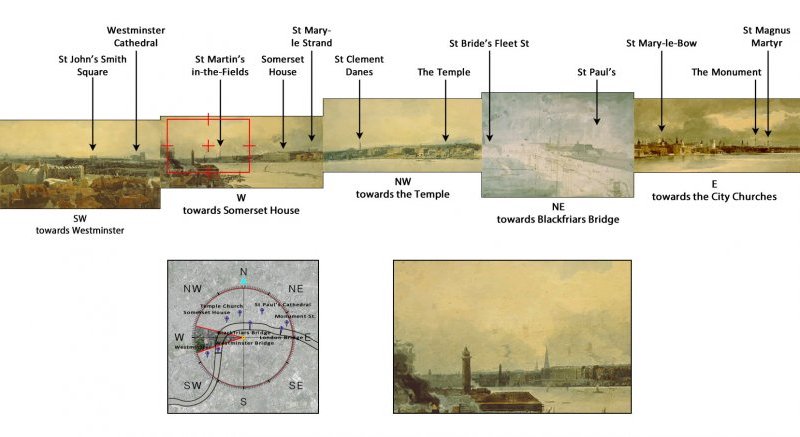

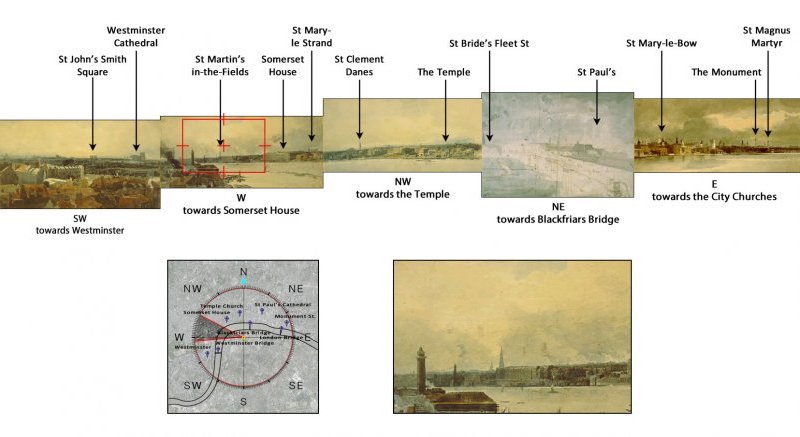

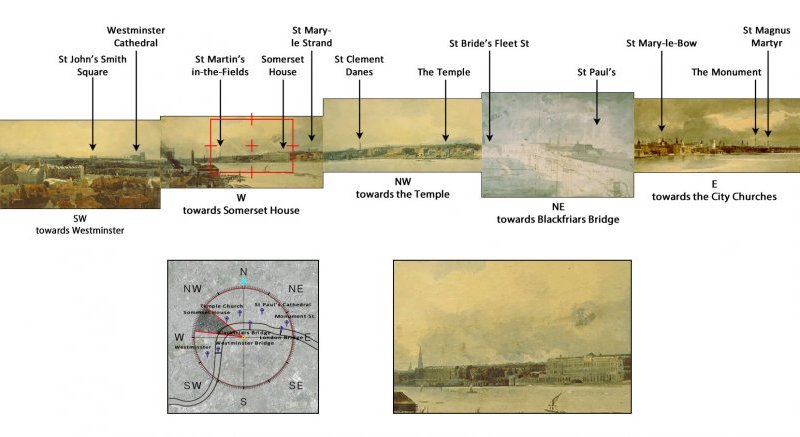

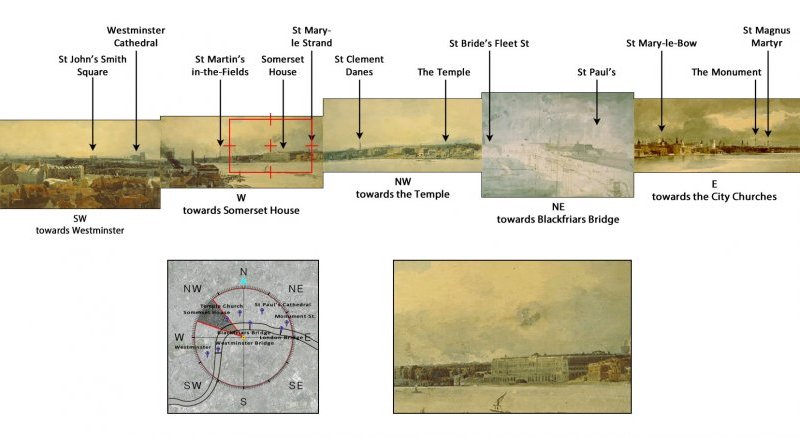

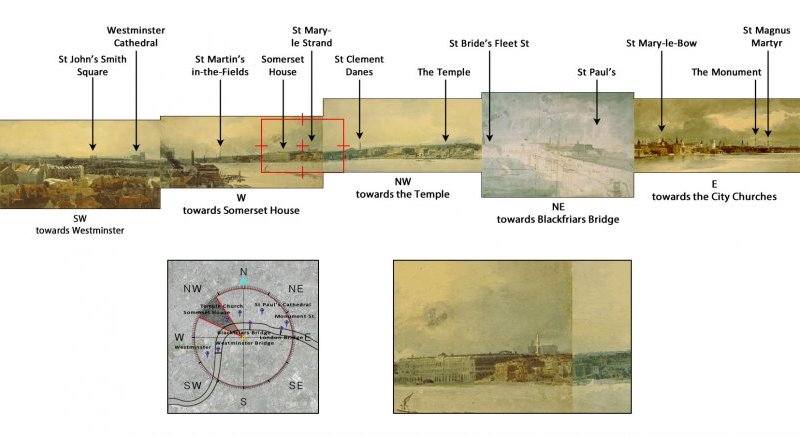

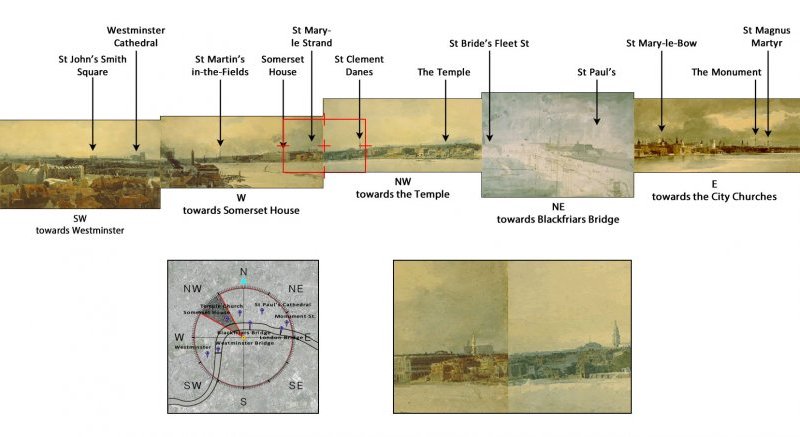

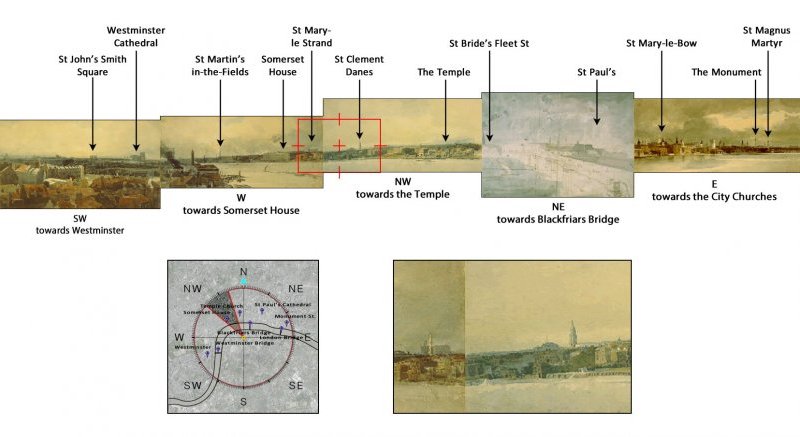

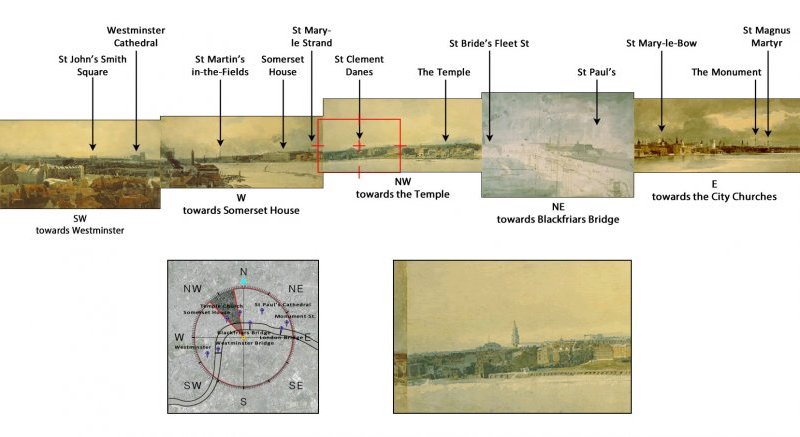

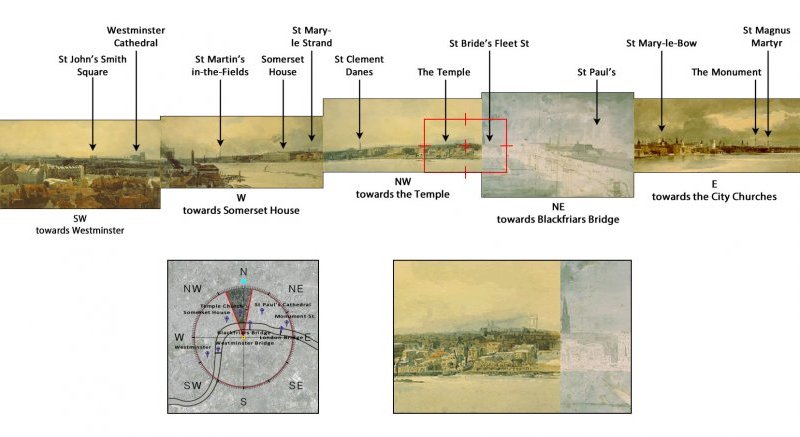

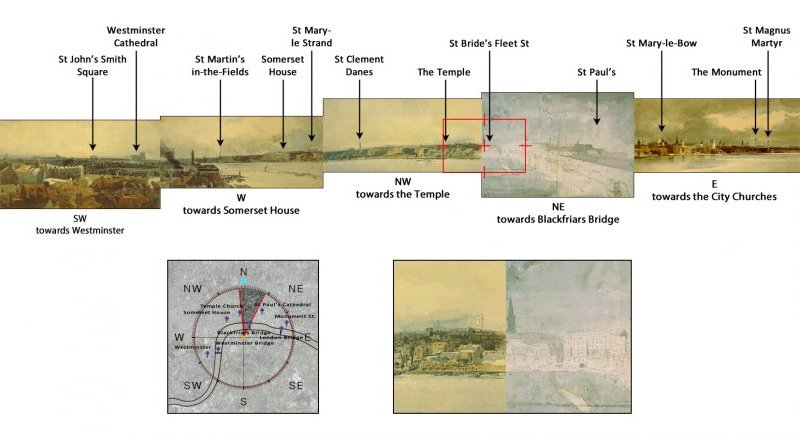

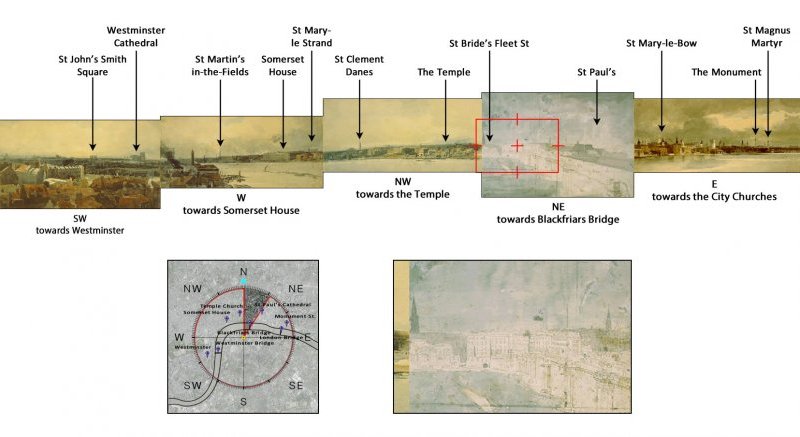

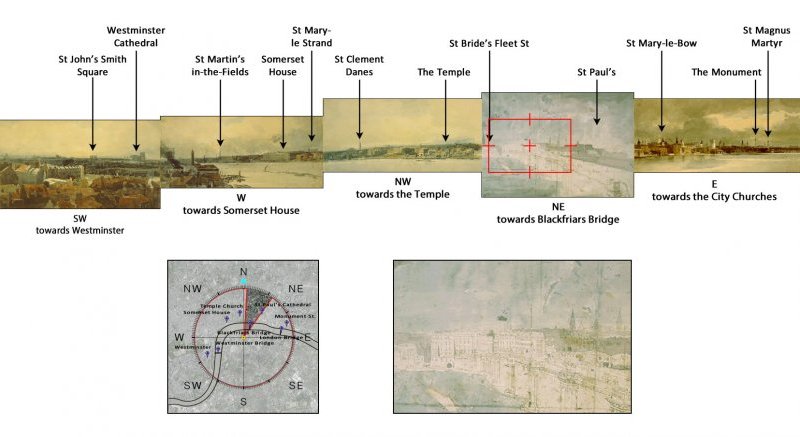

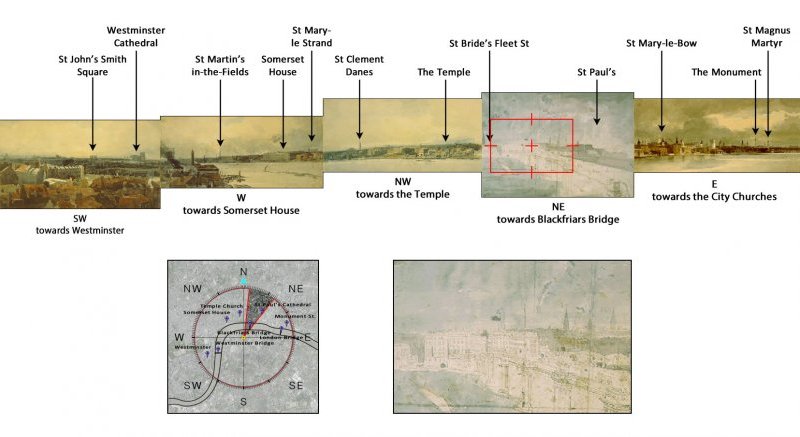

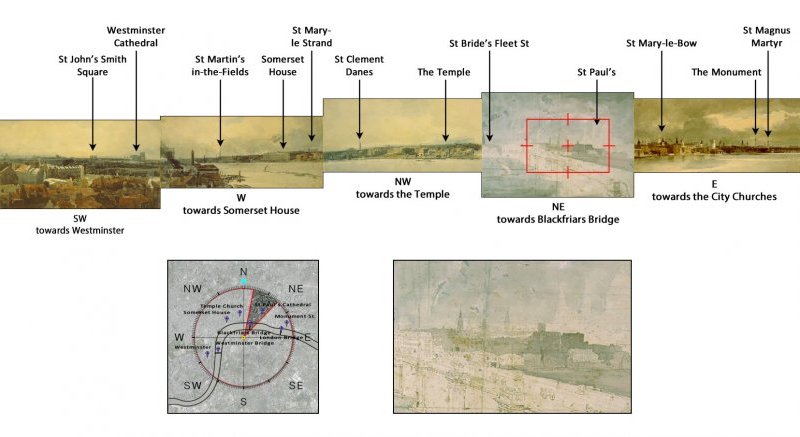

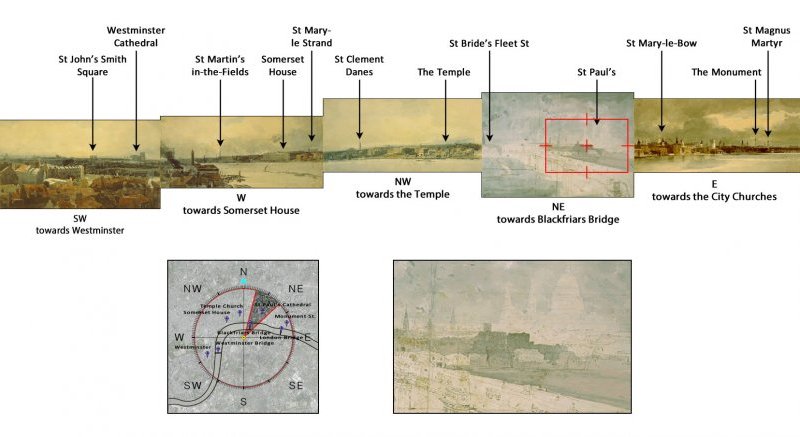

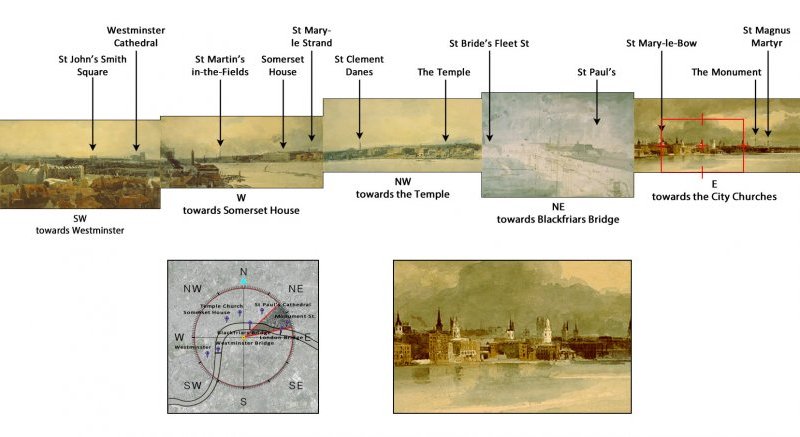

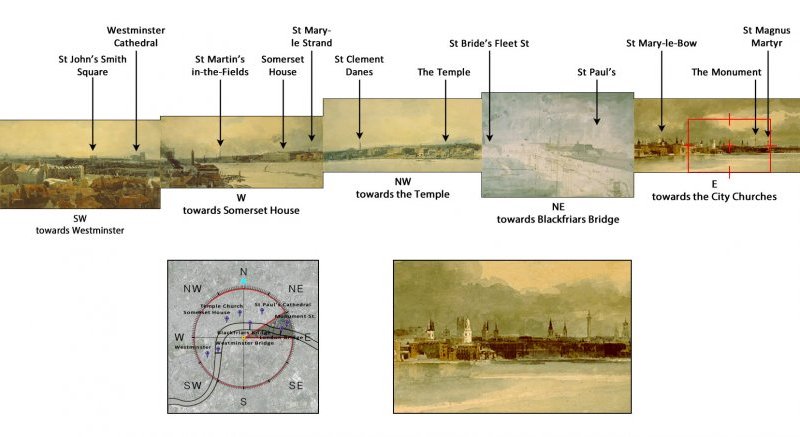

Girtin’s panorama

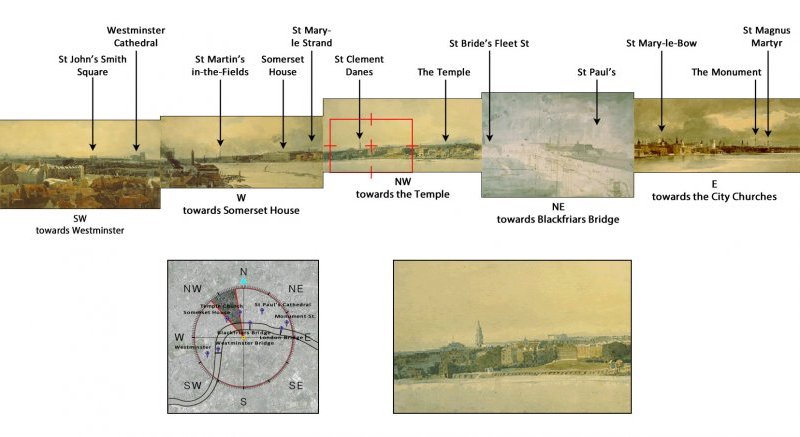

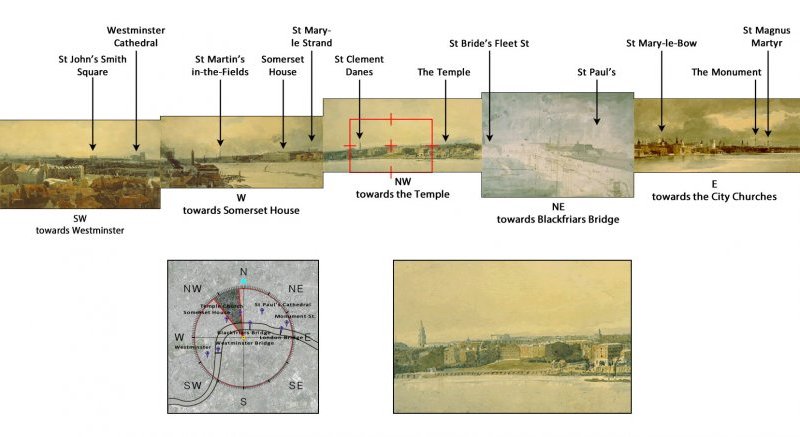

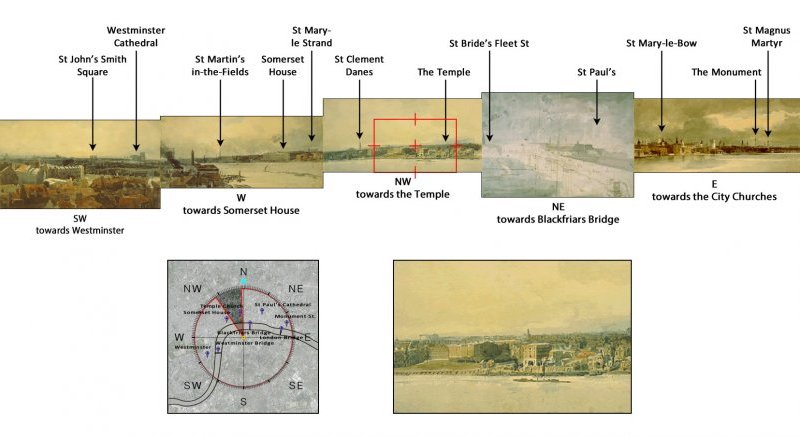

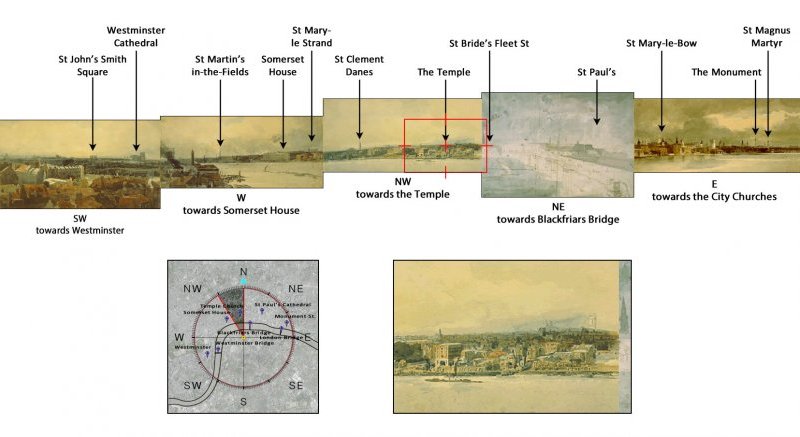

The painter Girtin created a panorama of London named Eidometropolis made of juxtaposed panels on an interior circumference.

The cityscape having become broader than the spectator’s field of vision, the visitors placed in the centre could not see the whole at one time ; giving a sweeping glance at the paintings, they saw the several parts of the panorama in succession.

They thus enjoyed the real life sense both of being surrounded by the cityscape and of framing part of it in their visual angle. Such an increased feeling for spatial vastness and multiplicity is a feature of the early nineteenth century.

This experience is evoked by the animation.

In this backlighting effect, the shadows are emphasised.

- W

- towards Somerset House

St Martin’s-in-the Fields St Mary-le-Strand

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

In this view of Somerset House, Girtin made a careful study of the reflected shadows and their colouring.

An animation shows the various steps of the design of shadows.

- NW

- towards the Temple

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

NE - towards Blackfriars Bridge

- NE

- towards Blackfriars Bridge and St Paul’s

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The viewing point was just above Blackfriars Bridge

In this circular vision, the horizontals predominate in the marginal areas (next section), the near verticals of orthogonals for Blackfriars Bridge (above).

The buildings assume unusual oblique relations, as if suspended in the limitless atmospheric luminosity of romantic painting.

“the artist ... has generally paid particular attention to representing objects of the hues which they appear in nature, and by that means greatly heightened the illusion. For example, the view towards the east appears through a sort of misty medium arising from the fires of the forges, manufacturers etc”

(1802 review)

In this circular vision, the horizontals predominate in the marginal areas (above),

the verticals of orthogonals for Blackfriars Bridge (previous section);

The buildings assume unusual oblique relations, as if suspended in the limitless atmospheric luminosity of romantic painting.

The shadow effects have been carefully studied.

Girtin’s panorama - Animations

- See the animation in full screen

| 1. The outline of Somerset House |

| 1. The outline of Somerset House | 2. Shadows under the arches |

| 1. The outline of Somerset House | 2. Shadows under the arches | 3. Light reflected under the arches by the water and by the strand, which lightens the shadow under the arches and emphasises the obliques |

| 1. The outline of Somerset House | 2. Shadows under the arches | 3. Light reflected under the arches by the water and by the strand, which lightens the shadow under the arches and emphasises the obliques | detail |

- (to the West) the darker cast shadows of the projecting parts - dormer-windows and chimneys

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- These self-shadows containing reflections in the recessed parts of the building differ from:

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- (to the East) the shaded areas behind the steeples which are of a dark warm colour if the steeple is in full light and of a dark cool colour if the steeple is under a cloud

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

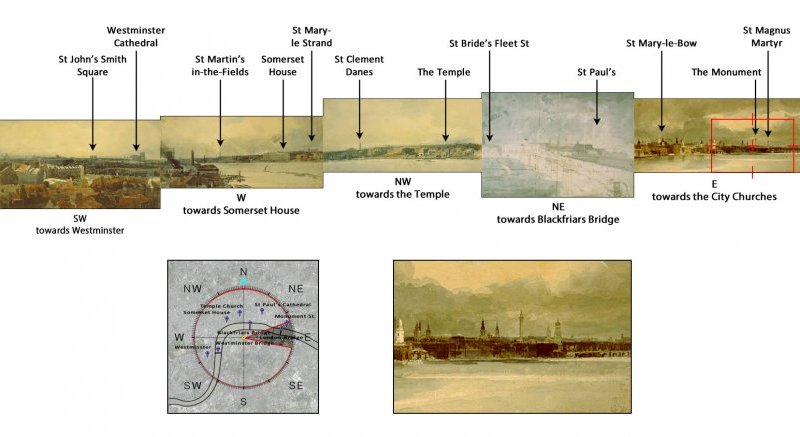

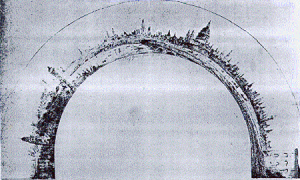

Etching after Girtin’s panorama

The dimensions of Girtin’s panorama have been questioned : it was announced as 108 feet long and 18 feet high ; the seven panels (the five ones showing the North bank and two turned towards the Southern suburbs) would thus be some 15 feet broad (squarish) and the radius of the circle 17 feet - again similar proportions.

But the watercolours are long rectangles. Other proportions have been proposed :

9 feet by 216, which would make each panel very elongated (31 feet - more than three times its height) and the radius of the circle 34 feet.

The panorama was entirely circular, though Francia’ s etching transforms the circle inot a semicircle for better legibility at one glance (the walls at both ends of the semicircle actually belong to the same building).

- Etching after Girtin’s panorama

- (British Museum)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The contemporaries were struck by the characteristics of panoramic presentation : the accuracy of the perspective (being used to the composite townscapes of previous painters, they regretted the lack of such “pictorial licence”) and its unfolding quality guiding the eye in several directions (it was necessary to send a disclaimer that it was not “a picture framed”). They also noted the sense of townscape relating the distances and the atmospheric perspective.

Contemporaries

“as it has been conceived to be merely a picture framed, he further begs leave to request the notice that it is a Panorama, and from its magintude which contains 1944 square feet, gives every object the appearance of being the size of nature. The situation is so close as to show to the greatest advantage the Thames, Somerset House, Temple Gardens, all the churches, bridges, principal buildings, etc. with the surrounding country to the remotest distance interspersed with a variety of objects characteristic of this great Metropolis”

The Times, 25 August 1802

“the wonderful array of buildings and towers as well as the elegance of Blackfriars Bridge”

The Morning Post and Gazetteer, 22 October 1802

"in the very first class in this new and extraordinary appropriation of perspective to painting. The artist, it seems, did not take the common way of measuring and reducing the objects, but trusted to his eye, and has by this means given a most picturesque display of the objects that he has thus brought into his great circle ; and, added to this he has generally paid particular attention to representing objects of the hues which they appear in nature, and by this means greatly heightened the illusion. For example, the view towards the East appears through a sort of misty medium, arising from the fires of the forges, manufactures, etc. which gradually lessen as we survey the western extremity.

Blackfriars Bridge is a prominent object, and St Paul’s rises with the utmost majestic dignity above the surrounding buildings. Though the Temple Gardens and some other parts are of a much lighter tint than the general masses, the whole is is harmony, and the eye is not hurt by spots. The water is pellucid and, contrary to what we have seen is the pictures of this description, varies in colour ; that near the shore very properly partaking of the hue of the earth beneath. The craft upon the river is boldly and forcibly relieved ...

The apparent space which the objects seem to occupy, and their relative size, give them the appearance of being much larger than they are. The person who attends the visitors measured one of the figures, which proved to be only four inches high ....

The two towers of Westminster Abbey appear in one mass, which destroys that lightness and air which constitutes a leading beauty in the building. From the point of view from which it is taken it is probably a true representation, but a licence is allowed to painters as well as to poets ; and where a picturesque effect can be produced, be overlooked or forgiven.“The Monthly Magazine and British Register,”Montly Retrospect of the Arts" 0ctober 1802, XIV, 254-55.

“The accuracy of Mr. Girtin’s eye was such that every house was attended to; all the churches, bridges, the Thames etc, with the numerous craft, Blackfriars Bridge and the Surrey Road ; and embellished with the astonishing variety of objects that characterizes this great commercial city .... the smoke floating across the picture from Lukin’s foundry, the impending storm over the City, and the grandeur of St Paul’s”

Henry Bate-Dudley, The Morning Herald , December 1802

“the most classic picture that has yet been taken in that brach of art, which may fairly be denominated the triumph of perspective”

The Gentleman’s Magazine, February 1803