Bristol

- The setting

- The maps

- Views of the harbour

- The merchants’ city

- The trading city

- Architectural developments

- Streets and hills

- The Georgian House

- Clifton

Read also: Bristol in the Atlantic World

The setting

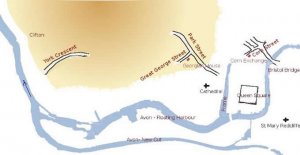

- Bristol map

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The harbour was founded in the Middle Ages at the confluence of the Frome (flowing North to South) and the Avon, which flows to the West towards the Atlantic. ’Bristol’ (formerly ’Bridgstow’ or ’Bristow’) means ’village (stow) near the bridge’.

- The right bank is hilly, so that, in addition to areas at river level, the city has areas built on sloping ground, and the Avon flows downstream through a gorge at Clifton.

- The Avon is a tidal river; the trading ships were dependent on the tide and would not be able to remain afloat at low tide, so that in the early 19th century locks were built on the arm of the Avon nearer the city to keep a constant level in the ’Floating Harbour’, while the tidal part of the Avon was diverted to another arm, the New Cut to the South.

- The Northern part of the Frome, shown here in blue like the other parts of the rivers, is now covered.

- Bristol Bridge, dating back to the Middle Ages, was the only bridge; it was several times rebuilt, in particular in the 1760s.

The maps:

- Bristol map

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The map above shows the natural setting and the major 18th-century areas.

- The map to the right is from John Rocque’s map of Bristol (1750), with the North obliquely in the top left-hand corner

- it shows that the area between the Avon and the Frome was largely built: Queen Square, Bristol bridge (the only bridge), the streets around the Exchange;

- to the West of the Frome only the area North of the Cathedral is built, but not the hills;

- to the South East beyond the bridge the Redcliffe area is also built.

Views of the harbour:

- The harbour

- The confluence of the Frome and the Avon

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Present-day photos:

- (photo to the immediate right/brown arrow) the confluence of the Frome and the Avon, with the mediaeval city close by - the cathedral is visible- and the hill in the distance

- (photo below /blue arrow) the Floating Harbour, view towards the gorge at Clifton to the West downstream with the rocks in the distance.

- The harbour

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Paintings:

- You may see the opposite upstream view of the Floating Harbour towards Redcliffe in the East (1826), by Samuel Jackson, at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

- It should be remembered that images are representations of the artist’s (and his contemporaries’) idea of the scene, rather than visual records; see Steve Poole’s article ’Visualising the City’ in Bristol Historical Resource (2000).

![]()

![]()

Click on the photos to see arrows on the map indicating the standpoint and direction of the view.

The merchants’ city

- The harbour

- View towards the Redcliffe basin (the same sightline as in Jackson’s painting mentioned above), an engraving from a drawing by W.H.Bartlett, for The Ports, Harbours, Watering Places and Picturesque Scenery of Great Britain (1842).

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Bristol had long been a trading city. From the Middle Ages, it imported timber and furs from the Baltic, fish from the North Atlantic, wine from Bordeaux and the Mediterranean. It exported manufactured goods - brass, woollen cloth. With the opening of the Atlantic routes after the discovery of America, it exported goods to Africa in order to trade slaves from Africa to the West Indies and America, from which it imported indigo, sugar, cocoa, back to Bristol - the ’triangular trade’. It had good road and water links to the West country, and served as its outlet. It had 165 merchant ships at the beginning of the 18th century.

Its merchants had a national role; one of them, Edward Colston, was on the board of the London Royal African Company in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and is well known in Bristol as the founder of schools and almshouses.

Bristol’s merchant ships are at the origin of Robinson Crusoe (1719): a sailor stranded on a desert island in the South Seas, Alexander Selkirk, was rescued and brought back by a Bristol ship; it was there that Defoe met him and turned his story into a novel.

Bristol also played a part in industry; it had long established industries - glassware, pottery, metalware - especially brass (due to the closeness of coalfields and Cornish copper mines); Abraham Darby was first a brass manufacturer in Bristol in the early years of the 18th century, before moving to Shropshire and applying his techniques to his ironworks in Coalbrookdale.

Bristol was also home to scientists and writers; the Pneumatic Institute run by Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808), who used apparatus made by Watt and was connected to the Lunar Society of the Midlands, counted the young Humphy Davy as one of its members (1799), where he demonstrated the effects of gas to Wordsworth and Coleridge, before moving to the Royal Institution.

The first Methodist chapel, known as the New Room, was built in Bristol.

The trading city

- The Exchange

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The trading area

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the course of the 18th century, the population rose from 25000 to 68000; it was at first the second largest city in the country after London.

It had banks and trading institutions (right, a view of the business area), with (far right) the Exchange built by John Wood the Elder (the architect of Bath) in 1743; its clock is of a later date - the 1840s, when the railway arrived, and it has two hands to show both local time and ’railway time’ (London time, earlier by 11 minutes, so that passengers would have to arrive ahead of the local time to board their train, which ran according to London time).

Architectural developments

- Queen Square

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Queen Square

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Queen Square

The 18th century urban form of the square: Queen Square (in honour of Queen Anne), built in the early 18th century. Largely inhabited by merchants, it had backyards leading to warehouses on the quays.

View towards the North, showing the East side to the right (far left photo); view of the South side (left).

You may see a view of Queen Square (1824) by Samuel Jackson at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Streets and hills

- Streets and hills

- Park Street

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Streets and hills

- Royal York Crescent

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Street design had to take into account the hilly ground. The houses in Park Street (18th century, photo to the far right) have staggered cornices down the hill .

In the same area is the Georgian House, the home of an 18th century merchant, now a period-house museum (see below).

In Royal York Crescent (late 18th-early 19th century, photo to the right), on a slope, the lower floor is a basement, and a street runs above it; the first floor of the houses has balconies overlooking the city and harbour.

The Crescent is on the way to Clifton, the late 18th-century fashionable development to the West (see below).

The Georgian House

- The Georgian House

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The Georgian House

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The house of a Georgian merchant has been restored as a museum of 18th-century life. It is on the hill - the last house just visible to the right of the photo - the pinnacles of the cathedral in the lower part of the city are just visible to the left- so that even the basement rooms at the back (mostly used by the servants) would have windows.

It was built in 1788-91 for the West-India merchant John Pinney.

It contains information about the merchant rooms.

Clifton

- Clifton

- Clifton from a distance

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

A suburb of Bristol, high on the rocks overlooking the Avon gorge downstream, was Clifton; it became a fashionable area, preferable to the old city, in the late 18th century. The picture taken to the far right from a recess in the Avon shows the Georgian terrace houses of Clifton in the distance above the woods. The Avon flows towards the left (West) and turns to pass below the Clifton houses shown in the second photo - the supension bridge did not exist, having been built by Brunel in the mid 19th century. At the lower level below Clifton were the Hot Wells, a fashionable resort.

You may see a view of the gorge with the Georgian terrace houses perched on it (1836), by James Baker Pyne, at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.