Travels

Conditions and means

See the frontispiece of Ogilby’s Britannia (1675), a collection of long maps (strip maps) following the main roads which remained widely used in the 18th century: it shows how a journey was visualised, a long line joining a series of towns as landmarks.

- Ogilby’s Britannia (1675)

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the frontispiece:

Roads

The travellers are coming out of one of the London gates (the coat of arms of London is visible above the door), and, from the maps held by putti in the sky, we guess that they are taking the Great North Road since we see the cities of Lincoln, York and Durham.

They will encounter a bridge on their way.

Most of the characters in the engraving travel on horseback, but we also see a coach further along the road approaching the hill.

Maps

The engravings illustrated different mapmaking techniques. The characters on the right of the bridge are rolling a wheel on the path : this is a ‘’podometer’’, a wheel where the circumference is known, so that by counting the number of turns of the wheel and multiplying it by the circumference, the length of the path covered can be found. This is ‘’direct measurement’’.

The characters in the lower right-hand corner are seated at a table where numerous geometrical instruments are displayed, those used for map-making ; some are used to calculate angles (a theodolite), so that a map can be made by pointing them from the top of a tower to two other landmarks, and copying the angle between them on to the map.

The two riders in the middle of the picture hold a map showing the road they are taking. The characters at the table also have a globe showing the world at a different scale: it shows Africa.

In the distance, we see the sea, and ships as a possible destination.

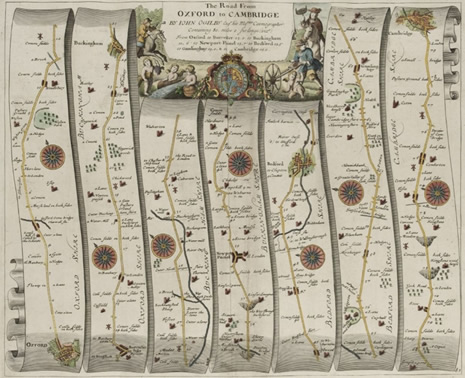

- The road from Oxford to Cambridge

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The example given here, the road from Oxford (lower left-hand corner) to Cambridge (top right-hand corner), shows the compasses pointing North: the journey starts northwards with the compass pointing almost towards the top, and when in the next strips of the map the road bends, it continues towards the top but with the compass inclined.

Coaches would have been driven by coachmen, with their traditional horn (still a symbol of postal services since coachmen of postal services would announce their arrival by blowing their horn).

The roads, though they were essential for trade and journeys between towns, were frequently bad, so that the ‘’turnpike’’ system was set up, as Parliament voted successive ‘’turnpike acts’’: at each turnpike (gates placed at intervals on roads), trusts levied tolls (a money charge) from those using the road, and used the funds for repairs. This improved the possibilities for trade.

To travel abroad: some itineraries that we now take for granted did not exist - some major roads on the Continent were built later, usually for military purposes, especially during the Napoleonic era. There was no land route along the French Riviera (as we call it now) to reach Italy; travellers would go to a harbour in the South of France and take a ship across the Mediterranean to harbours in Italy, for instance in Tuscany.

The alternative was to cross the Alps riding mules, a dangerous journey, so that travellers would not really enjoy the mountain landscape.

Destinations

A necessary part of the upbringing of an educated young man was ‘’the Grand Tour’’, a journey of several months through Europe which might provide him with useful experience of foreign countries, if for instance he later became a diplomat. There were also travellers who undetook such journeys later in life, possibly with their families, sometimes more than once, and left accounts of their visits to various places in Europe, usually in Mediterranean countries. The culmination of the tour was the various cities of Italy (still separate states, before Italian unification in the second half of the 19th century), to view the places mentioned by classical authors and by historians, and to acquire better knowledge of the fine arts, including city architecture - Venice was famous for its government, Florence as the birthplace of the Renaissance, Rome as the capital of the ancient world; Naples was added in the course of the century, especially after the discovery of Pompeii in 1758 (a Roman town buried under ashes by the Vesuvius): Sir William Hamilton, the British envoy, made studies of the vases found in the Naples area ; he was also interested in geology - the Vesuvius - and he patronized local artists who made views of ancient ruins and dedicated them to learned British men and women, to disseminate knowledge of Antiquity in literate circles in Britain. In the travel narratives that visitors wrote abour their journeys, they showed their knowledge of art history and judged paintings in the light of traditional criteria such as drawing and colouring, as we find in the writings of Anna Miller (1776) and others.

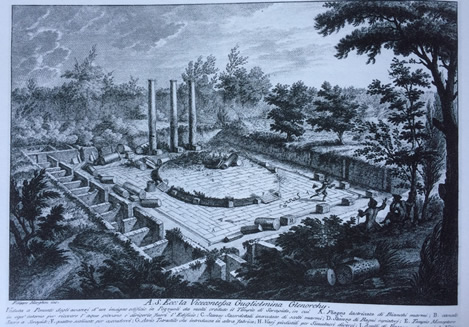

- View of the ruins of the ancient town Pozzuoli in the Naples area

- By Filippo Morghen

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

View of the ruins of the ancient town Pozzuoli in the Naples area (near Pompeii), by Filippo Morghen, printed under the patronage of Sir William Hamilton and dedicated to Lady Glenorchy, a Scotswoman involved in intellectual and religious activities.

Artists would make views of Italian cities in their natural surroundings.

See the view of Rome by Richard Wilson (1754, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff) it was actually a record of a traveller’s experience: this is the first view of Rome that visitors from the North have from the main road leading into Rome.

Florence seen from the surrounding hills was also a famous view:

- Florence from the road to Arezzo

- By Elizabeth Frances Batty, engraving, 1817

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Such Classical towns served as models for British cities: London, as a port city ruled by merchants, prided itself on being a new Venice ; in Bath, since its hot waters had been known to the Romans, the new Georgian parts of the city were built following the model of classical architecture with its columns of different ‘’orders’’; the New Town of Edinburgh was designed following a gridiron pattern imitated from Antiquity and described itself as ‘’the Athens of the North’’. Ancient objects would also be imitated: Wedgwood’s vases were meant as imitation of the antique.

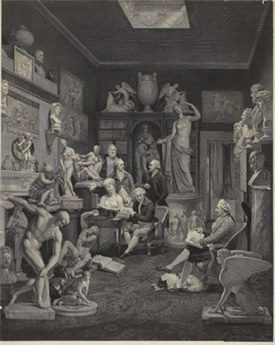

Travellers had their houses, or public buildings, built in imitation of Classical architecture. They also brought back ancient sculptures or replicas, so that their houses would be adorned in classical style as mementoes of their Grand Tour; they sometimes painted their house in ochre, a reminder of the usual colour of walls in Italian houses. Those who had taken the Grand Tour and could share memories would form clubs – the Society of Dilettanti, with an Italian name. Some famous collections of ancient sculpture were formed; see Charles Townley’s collection at his house in Westminster formed during his grand tours.

- Engraving after painting by Zoffany

- (1781, see the painting at Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museum, Burnley, Lancashire)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Some collectors opened their collections to artists so that they could study after the antique: another view of a different room in the same collection shows a young woman learning to draw from sculptures.

Memories of the Grand Tour would adorn their houses both in the country and in town, directly or indirectly. A Yorkshire gentleman, Sir Rowland Winn, adorned the library of his country house Nostell Priory in Yorkshire with partitions in classical style imitating columns, topped by pediments, with bas reliefs above, and ancient busts. Then he had a painting made of the library with himself and his wife in it (1767), which was to hang in their London townhouse in St James’s Square; thus the Grand Tour-inspired library in the country would be reflected in London thanks to the painting, and the decoration of townhouses would evoke rooms of artistic taste in countryhouses which were themselves inspired by distant Italian antiques.

As a part of their Grand Tour, they would have their portraits painted by Italian artists, in a classical landscape, with ancient monuments as a background and statues beside them: such paintings adorn their houses. See portraits by Pompeo Batoni, who frequently obtained such commission from British travellers on their Grand Tour.

Several British artists, like many other European artists, stayed in Italy as part of their training to study the Italian masters (see ‘’Painting’’).

In addition to visits to fashionable towns such as the spas - Bath, Tunbridge Wells -, travellers also started to explore more remote parts of Britain, including the mountainous landscapes such as Wales or the Highlands, and the Lake District, which suited the late 18th-century taste for the ‘’picturesque’’; this practice fostered the trade of landscape prints and illustrated travel narratives, which would be a new line in bookshops. The development of industry caused the advent of ‘’industrial tourism’’ to industrial towns: visitors would visit factories, or engineering feats such as Ironbridge. Foreigners who themselves owned land and factories would come over to find ideas to develop them: the ceramics factory of Wedgwood has records of plans made by ‘’Russian foreigners of distinction’’ or ‘’gentlemen from Petersburg’’ or Russian princes to visit the place, between the 1770 and the 1790s.

Ambassadors or envoys and their retinue would discover other countries, which was one of the channels through which news of foreign lands would reach Britain. Among the most famous, we have mentioned Sir William Hamilton in Naples, who published his discoveries in archaeology and geology (see above ‘’the Grand Tour’’). Also, the wives of ambassadors would gather information on the customs of the countries in which the couple was posted; Lady Wortley Montagu (1698-1762), wife of the ambassador to Constantinople (from 1716), informed the British public of the Turkish practice of ‘’inoculation’’ against the smallpox.

They would travel, primarily to other European cities, for their business. In the fashion trade, the practice was to find ideas or import object from Paris, and the ‘’poupée française’’ - a doll dressed luxuriously showing the latest Paris - fashion would travel throughout Europe even in time of war.

Voyages to distant lands such as the Pacific, starting from the usual military ports, had both a military and scientific purpose - demonstrating scientific and technical advances and making trials of them, in keeping with the development of trade and territorial expansion.

Cook sailed fom Plymouth on the Endeavour in 1768 to explore the Pacific. The Endeavour was a North Sea collier (a trading ship used to transport coal) adapted for this new purpose at the Royal Dockyard in Deptford, chosen because it was flat-bottomed to reach the beach easily: this shows how transfers between trading harbours and military ports worked. Cook was chosen as a naval officer because he was known as an expert cartographer with scientific practice as well, since the expedition had a scientific purpose : to see the ‘‘transit of Venus’’ (the planet Venus passing in front of the Sun as seen from the Earth) in the South Pacific, under the auspices of the Royal Society - this might give a scale to measure the solar system, by triangulating its appearances from two different viewpoints. The equipment, such as astronomical quadrants or sextants, telescopes, were provided by famous London scientific instruments makers - Ramsden, Short, Dollond (sextant) - which shows the role played by the skilled technologies from cities in overseas exploration. The purpose was also to chart the newly-discovered lands and bring back specimens of plants to enrich collections at home so as to serve as a basis for the advancement of natural sciences. In his later voyages, Cook used Harrison’s H4 time-keeper to chart the areas visited (see ‘’Astronomy’’ on the use of time-keepers to identify longitude) which led to much more precise maps of the Pacific. Artists would accompany expeditions and find original styles to render unknown types of landscape such as ‘’ice islands’’ in the regions near the South Pole.

Scientific collections were formed out of specimens collected in all parts of the world: a doctor, Sir Hans Sloane, who worked in Jamaica, wrote a book of natural history based on his observations (1707-25), and he added to his collections specimens sent by friends or bought from travellers from America and Asia. He assembled them in his London homes, first in Bloomsbury Place and then in Chelsea (where his name survives in Sloane Square), and he bequeathed them, with his collection of coins and books, to the nation on condition that they formed a museum open to the public; complemented with libraries dating from the 17th and 18th centuries (Cotton library, Royal Library), it was founded by Parliament in 1753 as the British Museum, in the Bloomsbury area. The present building, close to the location of the original building, dates from the 19th century. So major cities started containing museums which were microcosms of the world with specimens obtained from long-distance travels.

Private houses would also have decorative objects coming from exotic places: mahogany furniture and porcelain from China for instance, as well as objects from precious minerals; exotic drinks such as tea, coffee and chocolate would be favoured in the drawing rooms.

Life at home would thus reflect both classical and exotic travels, varying according to the taste of the inhabitants.

Travel writing

In addition to guides, there were travel accounts, in particular of the ‘’Grand Tour’’ (see above’’Destinations’’) ; such writings about the Grand Tour could become a literary genre in their own right, ranging from letter-writing (the essayist Addison, A Letter from Italy, 1704, or the poet Gray’s letters, 1739), to reflections on history with the philosopher Gibbon (1764) and then to emotional expression with Beckford’s Dreams, Waking Thoughts and Incidents; in a Series of Letters from Various Parts of Europe (1783). Such writings fashioned images of Italian cities in the public imagination: Florence surrounded by hills and containing treasures of Renaissance art; Venice a combination of palaces on canals and vistas towards the laguna; Rome as an eagerly expected ultimate destination of the journey.

Travellers visiting Britain also wrote about their journeys; Bath was described in the form of letters by the Reverend Penrose and in the form of a diary by Elizabeth Giffard. (both 1766). Edinburgh was described by Edward Topham in Letters from Edinburgh Written in the Years 1774,1775.

Some travellers discovered both the more remote and wild landscapes, and the newly industrialised areas. Dr Johnson visited Scotland in 1773, both the cities and the islands, and he visited the philosopher Lord Monboddo; he published A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland in 1775. He also wrote letters about his 1774 visits to industrial areas such as Derby.

‘’Picturesque’’ travel to Wales, the Lake District and Scotland was initiated by the books of William Gilpin adorned with engravings, all titled Observations … relative to picturesque beauty, first on Wales (1770, published 1782); then on the mountains, and lakes of Cumberland, and Westmoreland (1772, published 1786), and on the High-lands of Scotland (1776, published 1789).

Some novels were based on travelling as a structural theme: Smollett’s Humphry Clinker takes the forms of letters written by characters who travel through Britain and each see the scenes through their own point of view, which gives contrasting descriptions.

Painting

Townscape painting (a modern term) was called ‘’veduta ‘’ (plural ‘’vedute’’), an Italian term for ‘’view’’: the first views of cities were those of distant places, made by travelling artists for travellers interested in other countries, and conversely views of British cities were initiated by painters from other countries (see Painting).