Liverpool

The harbour

- A present-day view from the docks showing the width of the Mersey

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The docks date from the 18th century, mostly rebuilt and extended in the 19th century. Liverpool prospered from the late 17th century since merchants from London fleeing the plague (1665) and the fire (1666) settled in Liverpool.

Liverpool, as a harbour, has the advantage of being close to the sea near the mouth of the Mersey (3 miles), but at the same time with the ships protected in the docks.

The closeness to the sea had a drawback: the Mersey is a tidal river, which is a hindrance for the loading and unloading of cargo; some boats would remain on the mud, and larger ships would have to moor in the middle of the river and have their cargo unloaded by small boats; so docks were built. The Old Dock (1715, covered in 1826) was built by the engineer John Steers on the tidal inlet known as ’the Pool’ at the mouth of small local rivers, from which the town takes its name (the Liver is a mythical bird). It was the first commercial wet dock in the world.

The solution to the high tides (11 meters) in the 18th century was to close the docks with gates during the operations; in the 19th century floating landing stages on the Mersey were built, linked to the land by articulated bridges.

- Liverpool Docks (18th-early 19th c.)

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the 18th century, the docks were under the authority of the town council, except the Duke’s Dock (1773) which belonged to the Duke of Bridgewater, whose canal reached the Mersey at Runcorn (upstream from Liverpool).

The docks were open to the town; in the 19th century, in most harbour towns the docklands became a separate area, frequently walled around.

Then and now:

- the Liver buildings dating from the early 20th century, which now form Liverpool’s famous waterfront, are on the area created by covering St George’s Dock in 1900.

- the Albert Dock, the best known nowadays because it houses the ’Tate Gallery Liverpool’ and other cultural venues in its converted warehouses, was the first to be entirely surrounded by warehouses; we should not imagine the 18th-century docks on this model.

- Liverpool is now a World Heritage Site; you may find about the history of the docks.

Trade

- A view of the Mersey

- From G. Lancashire Illustrated (1831)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Transport:

- Liverpool was linked by canals to coal mines and to Manchester, then to Leeds by the Liverpool and Leeds Canal which, continued by the Aire, is linked to Hull on the North Sea.

- Short rivers were made navigable, with canal sections, to bring coal and salt from the neighbouring mines to the harbour - such as Sankey Brook canal from St Helens’s coalfield (1757).

- Road access also developed: in 1726 a turnpike trust was formed.

Commerce:

- Liverpool exported Lancashire coal, Cheshire salt and manufactured goods from Manchester (cotton) or from the Midlands (potteries and metal goods).

- A view of the Duke’s Dock with its warehouse

- From C.Pyne, Lancashire Illustrated (1831)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- It practised the ’triangular trade’: exporting goods to Africa in exchange for slaves, who were transported to America or the West Indies in the ’middle passage’, and sold against goods from those places to be imported to Liverpool.

- It imported goods both from other English regions and from overseas:

- from England, coastal trade being safer than land transport, it imported goods such as clay from Cornwall for the Staffordshire potteries.

- From overseas, it imported raw cotton for the textile industries at Manchester, rum and sugar from Virginia and the West Indies, ivory and timber from Africa.

The growth of trade: in 1710 the tonnage was 16000, in 1752 32000, in 1770 84000, in 1790 260 000 (according to a 19th-century newspaper).

The capital generated by trade was one of the factors contributing to the development of industry in the neighbouring Manchester area.

The city:

- The population grew from 5000 in 1700 to 12000 in 1730, 26000 in 1760, and 77000 in 1800. In the 1730s it already had a trading fleet of 131 ships.

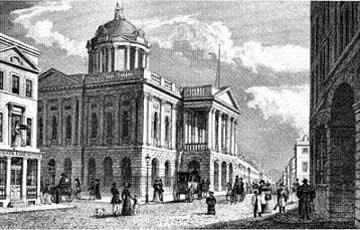

- An engraving of the Town Hall

- Also by Pyne. The dome and portico are a later addition.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The Liverpool ’corporation’ (town governing bodies) was one of the richest in England, and it had income from the docks which contributed to improve them. In 1786, it set up an ’Improvement Committee’ for the town.The debt incurred in improvements was serviced by income from the docks, not added to the rates paid by the inhabitants as was done in other towns (which needed an act to allow for the increase of rates).

- The townhall was built by John Wood (1754), the architect of Bath. Behind was the place, known as ’the Exchange Flags’, where cotton brokers carried on their negotiations.

- From 1786 onwards, as a result of an Improvement Act, an Improvement Committee was appointed to ’consider the best methods of improving the town’; it widened Castle Street leading to the Town Hall front and built stucco terraces with columns along it; the debt incurred by the corporation was serviced by income from the docks.