Rising industrial centres

- Birmingham ,

- Derby ,

- Ironbridge ,

- Leeds ,

- Manchester ,

- New Lanark ,

- Sheffield ,

- Stourport ,

- The Potteries , )

The location of trades in pre-industrial times

Watermills had been a source of energy for several centuries; their wheels were used to drive machinery, in particular mechanical hammers. Ponds which fed such watermills are still called ’hammerponds’, a mark that such a water-powered hammer-based workshop was nearby.

Areas in valleys with streams descending from mountains, in particular the valleys of the Pennine hills with streams flowing towards rivers emptying in the North Sea, had factories:

- textile factories, still called ’mills’ because they originated as machinery driven by watermills;

- metal works, using the streams

Mines and related crafts had existed long before the industrialisation age of the late 18th century; in several cases they were located in regions which later ceased to be industrial areas.

In the South West, Cornwall had been known since Antiquity for its mines, especially tin mines; from ancient times, ships from the Mediterranean sailed into the Atlantic to reach it.

In the South East, the Weald was an area known for its furnaces.

In the North East, coal extraction took place near Newcastle and was exported to destinations in England (such as London) by boat on the North Sea; so that in the Renaissance ’to carry coal to Newcastle’ was a proverb meaning ’to give something to someone who already has too much of it’. The area remained industrial.

Though several of these areas ceased to be industrial regions, they played a part in the industrialisation process.

When a problem arose in the Cornish mines - surface metal resources were exhausted in the early 18th century, and it was imposible to exploit the deep mines because they were frequently flooded -, it became necessary to invent pumps. The first steam engines were designed to activate pumps for the Cornish mines, by Newcomen; he experimented his first engine in the coal mine of the Earl of Dudley, near Birmingham, in 1712 (a replica is now working in the Black Country Living Museum).

They were later applied to numerous other machines, contibuting to the wave of industrialisation which was based on the new source of energy - first machines in factories, with low pressure engines, then transport by railways, which needed high pressure and became possible later.

The location of industries in industrial times

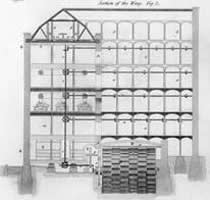

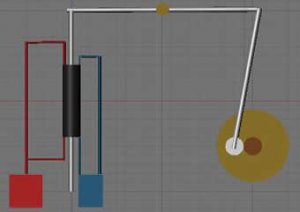

- The Watt engine

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Industries concentrated in the Midlands, due to several factors:

- raw material (coalfields)

- the development of machinery

- transport was vital to industry; however, their requirements were sometimes contradictory: watermills needed waterfalls but these were a hindrance on waterways, and locks had to be built to by-pass them.

Industries were located not only in towns but also in the neighbouring countryside, for several reasons:

- closeness to material and sources of energy

- closeness to the labour force (cottagers and their families)

- better confidentiality of industrial secrets in secluded villages

Industrialisation and urbanisation

- Stourport

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The two processes are interlocked but do not entirely coincide

The first buildings marking the beginnings of the factory system (workers grouped in a large building of a new type or ’factory’, mechanisation) appeared in rural areas still dependent on water power such as the Pennine Valleys: Cromford on the River Derwent near Derby, New Lanark in Scotland, for the textile industry.

These areas gradually became small towns with lodgings and public buildings for the workforce.

With the advent of steam power and the availability of energy (coal) due to improved transport, the factory type was transferred to large towns like Manchester- the seclusion of the Derwent Valley mills away from transport became an impediment.

Owing to the importance of transport, new towns appeared in rural areas at transport junctions, especially canals: Stourport-on-Severn at the junction of the Staffordshire and Worcester Canal with the Severn.

The development of transport between towns, due to industrialisation, had an effect on the perception of the landscape and of journeys through it, with either circuitous contours or more direct routes needing engineering works.

Urbanisation, towns and cities

The economic role and the political role of towns could be in contradiction; the constituencies having been fixed in the Middle Ages, long before industrial towns appeared. Manchester was considered as a ’village’ and had no representation in Parliament until 1832, and Birmingham was only represented through its county (Warwickshire).

The newly powerful industrial towns frequently had limited municipal institutions and government, as when they were small villages - some had no ’corporation’. This was a political drawback, but some contemporaries argued that it meant a lack of ’shackles’ which favoured economic development and attracted industries (see Hutton’s views on Birmingham, 1782).

Industrial architecture and landscape

Factories were large buildings, with a larger number of storeys and bays, and thus a more repetitive pattern, than in classical architecture, but frequently attempting to preserve satisfactory external proportions (see Halifax)

The interior layout corresponded to the needs of mechanisation:

- areas and stairs for circulation

- some storeys entirely open space to allow for machinery or spreading of sails (see Chatham)

- horizontal and vertical corridors running through the whole building to house the main shafts driving the machinery and transmitting movement to all the storeys; there were attempts to use classical architectural motifs and adapt them to such uses, such as a projecting building to house main machinery (see Masson Mill)

Fireproofing was an issue, and was addressed in the early 19th century (see Belper and Armley Mills)

High windows were needed.

Artificial lighting: candles, and experiments on gas lighting in the last decade of the 18th century, which was less likely to provoke fires, and had much more luminosity.

Rumford’s experiments in the late 18th century contributed to establish the unit of luminosity, the ’candle’: a source of light is said to emit two, three... ’candles’, if its light can be concealed with two, three ....of the screens needed to conceal the light of a candle; his experiments established the number of ’candles’ of a gaslight. He also used a ’shadow photometer’ - comparing the relative distances of two sources of light to a screen when they cast shadows of similar intensity .

In factories, gaslight was therefore useful to have brighter working places. It was used in the Soho Foundry (Birmingham) in 1798, then outside it in 1802.

The first streetlighting with gas was in London - in Pall Mall - in 1807.

Synchronised work meant more accurate timekeeping; clocks became features of industrial and commercial buildings, and experiments were made on devices registering work hours .