Bristol in the Atlantic World

Bristol in the Atlantic World: Trade, Slavery and Abolition

The city of Bristol proudly claims its commitment to maritime the exploration that took place centuries ago. Bristol does honor figures known for being adventurous and for having sailed the oceans as conquerors. The city has indeed a long maritime history. During the Middle Ages, Bristol established links with other European ports. Initially the port dedicated its activities to fishing. David Walker [1] contended that it was because of its relative proximity to London, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland that William the Conqueror chose Bristol to rival with London’s architectural beauty. In the 11th century a tower said to have been as important as the Tower of London was built in Bristol. Archaeological findings suggest that Bristol was already a thriving provincial port that could compete with others (such as Plymouth for example). As far as historical and archeological findings are concerned, silver coins made under the reign of King Cnut (1016-1035) were discovered in Bristol. In addition, the Doomsday Book commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1085 and completed the following year, showed that Bristol was the fourth largest city after London, York and Winchester.

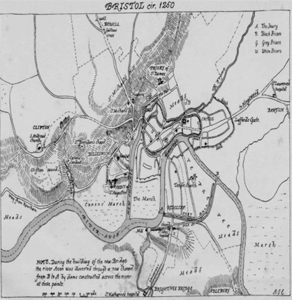

- Map of Bristol (1250)

- Map of Bristol as it was in 1250, B.R.O: 39801/X/11

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

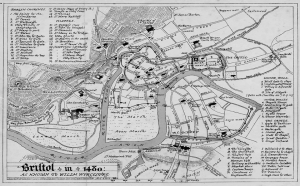

- Map of Bristol (1480)

- Map of Bristol in 1480, “as known to William Wyrcestre”, B.R.O: 39801/X/12

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

These images are 2 centuries apart. However big the city looks. This is not unusual but it is interesting to see what changed. 34 parishes meant more people. We have here a fine example of 13th century provincial urban planning.

The 16th century was a turning point for Bristol as far as trade was concerned. It is also an interesting period to study if we want to understand the bond that exists between Bristolians and their port city. The port benefited from links with 2 main rivers.

As we can see, a ship arriving at the mouth of the River Severn was bound to meet the River Avon and the River Frome, before proceeding to the dock. A ship going toward the River Severn was forced to go through River Avon before it could reach the Severn. The River Avon was so narrow that only the most skilled pilots could sail past obstacles. These included incoming boats. Unlucky pilots had to face spring tide on the Somerset coast. The tide could go up to 42 feet when reaching the mouth of the river Avon.

As time went by, the port and the city’s reputation grew. According to Jean Vanes, in the Middle Ages, a great number of sailors and captains from Bristol acquired enough skills to roam the Irish coast, the Barbary Coast, the North Sea. They even went up to what is called Iceland nowadays. These pilots and sailors were mostly of humble origin. They were also adventurers who saw opportunities for better lives, and they had skills to trade. They were willing to embark on enterprises that had great financial rewards. Not all of these pilots wanted to leave or could leave. In fact, the vast majority of River pilots stayed close to Bristol. They were mostly employed by the city and they generally lived at the mouth of River Severn.

Despite these positive points, the port was regularly suffering from lack of funds to undertake renovations. In the 16th century, officials decided that it was time to have a new wharf. Stone from monasteries and tombstones were used. The idea was to speed up unloading processes. Another issue needed to be addressed and it was the protection of the cargo. Theft was widespread but the ports officials were determined to enhance Bristol’s reputation. It was also the time when Bristol started to deal with questions about the tidiness of the docks. For example, orders preventing soap manufacturers to throw their waste into the river or boat manufacturers to cut wood near the river were issued. So were measures preventing citizens from throwing their garbage near the port. The penalty was a heavy fine. Port wardens were even hired. They were responsible for cleaning the port, helping unload the cargo and collecting taxes citizens had to pay for port maintenance.

Trade

Now, when we talk about the port, cargoes and goods, we think about exchanges and trade. Traders were indeed important people in Bristol in the 16th century. However it is really in the latter part of the 17th century that the power of leading merchants was strengthened. It started when merchants decided to deal with matters concerning the maintenance of the port. That shift of responsibly had unsuspected consequences on the trade in general and the transatlantic slave trade in particular. Indeed, what was only a matter of shared responsibility led to the extension of the port and to an increase in trading ventures. In the first part of the 17th century, merchants formed a corporation whose members did not hesitate to lend money to the city to allow it to survive when the city’s officials decided to remove a few tolls. The idea was to encourage more ships to come to Bristol. Strangely enough everyone did not respect merchants. Jean Vanes reported that merchants had to be cautious when dealing with sailors. Some captains did not hesitate to damage cargoes if they were unhappy about their pay. Some demanded a pay raise just before delivering the cargo.

One master is recorded as having abused the owner in English and Spanish, broken his whistle over his head, demanded fresh meat, soft bread, grapes and pomegranates, ordered repairs and fresh tackle, missed a favourable wind and made his landfall in Wales instead of on the banks of the Thames.

VANES, Jean, The Port of Bristol in the Sixteenth Century, Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 2000, p.14.

As the port became more prosperous, Bristol’s fairs and markets became one the city’s showcase for affluence. Foreign trade in the mid 16th century was mainly with Holland, Russia, North Africa, Italy, and other parts of the Mediterranean. Trade marked the 17th and 18th century with partners from the Atlantic world. Products imported from these places were essentially cloth, wine, fruit, spices and soap. France for instance provided Bristol with woad plant from Toulouse, resin, honey and paper from Bordeaux, salt, and canvas from La Rochelle.

Vanes mentioned occasional trips to the Guinea coast in West Africa. The pride Bristolians felt for city was based on economic success. These feelings actually started with the stories of early explorers. John Cabot was one of them.

As shown in Ernest Board’s painting The Departure of John and Sebastian Cabot on their First Voyage of Discovery, 1497 (painted in 1906, Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Object Number: K102), the Cabots, father and son are on their way to the Americas, 5 years after Columbus’s expedition. The population, including religious representatives and the city’s officials gathered on the docks to wish them fair wind.

The case of the Cabot family and other family stories are interesting to study because they show how narratives about explorations and conquest contributed to obscuring the devastating nature of the transatlantic slave trade.

John Cabot or Giovanni or Zuan Caboto was born in Venice. He turned to trade to make a living. As a merchant who traded with many foreign kingdoms he often came in contact with Muslim traders. He traded in fabrics, spices and other products that had been acquired by the Arabs in Asia. He moved to Spain with his family around 1490 because Spain and Portugal were dominating the Mediterranean trade the 15th century. Like many ambitious traders, Cabot wanted to find a protector in Spain. Spain was not interested. He moved to England in 1494. Two years later, he won the supports of Henry VII. The financial boost provided by his new friends allowed him to explore shorter routes to North America and Asia. He managed to reach the land that he called New Found Land in 1497.

In 2012, researchers from Bristol University made an interesting discovery: Dr Francesco Guidi-Bruscoli found out that Cabot actually received money from the Bardi banking based in London in April 1496. What it means is that Florentine merchants funded one of the first English expedition. That resulted in the first European presence in North America.

Let’s come back to the Cabots. His son followed his footsteps in relation to maritime exploration. Neither John, nor Sebastian Cabot fundamentally changed the way maritime exploration was made. That had little impact on their reputation. For Bristolians, they still epitomize the victory of men over the ocean, the victory of Christianity over paganism. Above all John Cabot was among the first provincial explorers to have secured the supports of the monarchy. He also had the support of local merchants in Bristol.

No wonder his story is filled with grandeur and perhaps myths. It is difficult to know precisely the maritime routes used by the Cabots and what happened to John. Speculations about parts of his life are based on letters Cabot wrote to John Day, another merchant around 1497. Sebastian Cabot appeared to have occasionally embellished the truth about his life or his explorations. Unlike his father, he had few connections with Bristol. That did not matter. Sebastian Cabot is known as a cartographer. Quinn notes that he merely added a few remarks about his own travels and those of his father to world map of 1544. One may wonder why such fondness towards the Cabots. As Quinn laments theatrically perhaps that he could ruin his father and his own reputation because of his lies and his taste for secrecy, but this was not the case.

A man of many talents, competent and far seeing in many respects, he was also vain, and in action arbitrary, while he lived a fantasy life of mysteries and dark secrets alongside his more prosaic every day activities

QUINN, B. David, Sebastian Cabot and Bristol exploration, Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1997, p.33

Narratives about the Cabots constantly use terms such as discoveries, success, exploration and conquest. Most local historians relay this fascination for people of Bristol about John and Sebastian and about other explorers who roamed the oceans with the support of powerful investors. They explain the need to annex areas of Africa and the Americas as being part of a long tradition in the history of city. Few narratives directly mention the transatlantic slave trade.

It is not the slave trade or the African trade that are at the heart of the study done by Donald Jones. The work is about the voyages of Captain Woodes Rogers in 1708 and 1711. Bristol merchants funded some of Woodes’s expeditions. They also wanted the sea captain to get rid of pirates threatening Bristol’s vessels that were on their way to the Bahamas. The letter of marque that had been given to Rogers stated that he could seize any asset aboard foreign vessels. Letters of Marque were used in times of war. They allowed private vessels to take enemies’ ships. From his trips, Rogers brought silk, precious metals and other products taken from a Spanish ship that he had attacked. All did not go smoothly. Once back in England, Rogers was threatened by the East India Company officials. The East India Company was an organization set up to manage trading ventures with Asia. The company believed that Rogers had encroached on their trading interest. The company tried to confiscate Rogers’ cargo. The English courts had to rule on the dispute. It is nevertheless as a hero that Rogers, Dampier (his second mate) and Selkirk arrive in England. Selkirk was a Scottish sailor who, after an argument with his captain, chose to be deported to the island of Juan Fernandez about 500 miles from Chile. Rogers rescued Selkirk from the island. These stories had an impact on people in England. Historian Dennis Reinhartz showed that Rogers and Dampier’s adventures inspired Daniel Defoe. The 3 sailors were inspirational characters for his novel Captain Singleton. Rogers and Selkirk inspired Defoe to write another book: the renowned Robinson Crusoe. Jonathan Swift also used these three sailors story for his Gulliver’s Travels. Swift and Rogers shared the same circle of acquaintances. Rogers decided to write his own story. He published Cruzing Voyage Round the World, in 1712. The need to romanticize Woodes’ adventures as Defoe and Swift did and the decision to present the story of his own adventures as a proof of what “really” happened resulted in a sacralisation of Woodes Rogers story. In other words it was not a story anymore but part of history and maritime history in particular. I won’t go into great details about this idea of sacralisation through testimony / oral history as defined by the Tzevetan Todorov, Paul Ricœur and Michel de Certeau but let’s just say from oral history to story telling to novel and then travel account, Rogers’ adventures have acquired an aura of truth and were turned into historical facts. In addition, the reader is aware that the adventures of Robinson Crusoe are fictitious of course but the fact that the story is based on a character that existed confers it some credibility and truth that is generally attributed to historical narratives. Incidentally, the search for authenticity is notable in Defoe’s novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe tried to analyse the relationship between Crusoe and Friday. The description is imbued with paternalist overtones but interesting as it presents the reader with the notion that savages can learn under proper supervision. By extension some 18th c intellectuals argued that ‘Children of nature’ can be baptized and learn (Wilberforce).

I have been talking about sailors and I mentioned merchants but who were they? How did one become a merchant?

In Bristol, merchants were part of the middle upper class then the upper class in the 18th century. They were a close-knit community that allowed only a few newcomers to join the group. Interestingly enough, merchants were often part of an old guild, whereas plantation owners managed to acquire wealth and it was only then that they could treat on equal footing with merchants. There was snobbery between those who got their hand dirty in the West Indies in the early days of the slave trade and those who traded in the metropolis. If was fine to acquire slaves and trade in African commodities but the constant contact that was part of plantation life was seen as being demeaning, or unsuitable for gentlemen. That did not prevent those who had the means to invest in plantations to also acquire them; simply because it was a lucrative investment. These people were known as absentee plantation owners. Who were these merchants?

In the 14th century most merchants from Bristol belonged to a guild called The Merchant Guild. In 1552 the guild became by royal charter, The Merchant Venturers society of Bristol. The society’s power increased over the next century. The society managed the port as well as trade, as we saw earlier on.

In the 18th C., several members turned to a trade that would prove to be lucrative on many occasions. The African trade involved trading in several commodities including enslaved Africans.

Transatlantic expeditions were costly and risky. They required important investments and committed investors. People who could afford to wait a few months before they could have a return in on their investment. It was more than ever important to trust fellow investors. That partly explains why merchants were a tightly knit group. These people were often linked through marriages. They also belonged to the same religious congregations. David Richardson noted that most merchants were directly from Bristol. They often came the same social and economic background. However, because of the nature of the investment needed for transatlantic expeditions, minority shareholders did not have to be merchants. Small merchants or sea captains could invest in those enterprises. In fact it was better if the captain of the ship that was to set sail to Africa and then to the Americas was one of the shareholders. He was more likely to pay special attention to the cargo.

I’d like to look at a few families who made a fortune through transatlantic expeditions. And as you will see, sometimes they appeared to have had little connections with Africa or with the slave trade.

The Goldney family is of particular interest. The links between the Golneys and Bristol date back to the 17th century. In 1637, Thomas Goldney left Chippenham to become an apprentice in Bristol. At the time people who wanted to practice a trade had to be freemen. Thomas Goldney served as an apprentice for many years (7 was a minimum requirement). He became a freeman in 1646. He married Mary Clements and opened a grocery. Thomas and Mary joined the Society of Friends meaning they became Quakers. In 1674, Goldney bought a country estate at Elberton, in Gloucestershire. He rented it. In 1688, he built 4 houses, and kept one of them for his personal use. Goldney I died in 1694. No strong direct links here with the slave trade.

His son Thomas Goldney II was born in 1664. He married Hannah Speed, the daughter of a Bristol merchant in 1687. He took on his father’s grocery business. He too invested in other ventures. He owned shares in ships, acquired land in nearby villages. He even became an agent for the Collector of Customs for the port of Bristol. We learn from PK Stembridge that by 1694, he was able to lease a country house in Clifton, now known as Goldney Hall.

He had become the main shareholder in a voyage from Bristol, led by no other than … Woodes Rogers. The voyage involved 2 ships and it was successful. Goldney’s initial investment was £3,726. He received £6,800. That was indeed an important return.

However what was the direct link with the transatlantic slave trade?

Goldney III was born in 1696. He also took on the family business and trading interests. He invested in iron works in Chester and North wales. In 1750, in partnership with William Champion, Thomas Goldney III invested in a mining business. That proved to be successful. So iron was used to make anchors and other parts needed in shipbuilding. It was also used to make manilas used to contain slaves among other things. Some of Goldney’s businesses relied on the development of transatlantic expeditions and the slave trade in particular in the 18th century. By 1751, he had officially turned to the shipping industry. He was involved in transport, mining, and manufacturing. A lot of money was involved. Goldney naturally turned to banking. In 1752, along with 5 associates, he formed the Goldney, Smith and Co. It was new a bank. We learn from the national archives that it was one of the first 6 banks to be established in the whole country. After his death the bank became the Harford’s Bank. It later merged with the Old Bank then with the National Westminster Bank, which is today part of the Royal Bank of Scotland.

One may argue that Goldney did not specifically invest in the slave trade but as we have seen his business had unavoidable connections with that trade.

Another example that shows that religion was not obstacle to the trade or to the slave trade. In some instances religious affiliation could be useful.

- 1685: The Dragonnades With the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, the French King Louis XIV stipulated that Huguenots should convert to Catholicism. Very few converted. Most left the country. They settled in neighbouring kingdoms. Some came to England and settled in Plymouth, Exeter, Barnstaple and Bristol. Ronald Mayo showed how integration went. It was not easy to say the least. Newcomers were French. They were ferociously attached to their language. They were reluctant to learn English. They represented a cost for the city even though Charles II’s policy was in theory, favorable to these refugees.

At a time when we were talking about integration, failed multicultural policies of integration, British citizenship, refugees, European common values, etc., I couldn’t resist reading this from Mayo’s work:

Mayo’s abstract

Charles II issued a brief or letter to be read in all Anglican churches appealing for funds for those of the refugees who were destitute. At the same time he granted to the immigrants free letters of Denization which conferred a restricted form of British nationality. […] The Corporation’s reaction to the situation was the one to be expected from any seventeenth century local authority administering the Poor Law. […] The Bristol Common Council was concerned mainly with knowing where the Huguenots were to be sent and where the money was coming from to feed them so long as they remained in the city.

MAYO, Ronald, The Huguenots in Bristol, Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1985, p. 9.

A few years later these problems of assimilation had disappeared. The Casamajors and the Laroche were among Huguenots who settled in Bristol. In 1704, Louis Casamajor found 2 partners and together they chartered a ship that delivered goods overseas. They made a healthy profit. We don’t know if Casamajor turned to the transatlantic slave trade. We know however that Jacques Laroche (the father and the nephew had the same name) did. They invested in that venture as minority shareholders then later on as majority shareholders in other expeditions. In fact, they chartered several slave ships during the 7 years War (1756-1763). Jacques Laroche was co-owner of the ship the Black Prince. That ship set to sail in Africa then to the West Indies (Antigua). It has been reported that the captain’s lack of skills and bad management led to a slave insurrection and to crew insubordination. James Laroche, 1st baronet is widely known nowadays as having been a Bristol slave trader. He was sheriff in Bristol, and then became master of the Society of Merchant Venturers in 1782-83. Later on he represented Bodmin in Parliament in 1768 and 1780.

The Laroches were not the only Huguenot families in Bristol to rise to fame and to invest in the transatlantic slave trade. The Peloquins are another example. Other non-Huguenot families had close connections with trade. John Anderson, John Fowler, Isaac Hobhouse, James Rogers and Noblet Ruddock were close relations of James Laroche. They formed the elitist group called agents, specialized in trading in slaves. David Richardson contended that these 6 men organized 400 transatlantic voyages. Laroche acted as agent for 130 of them thus becoming the most important agent in Bristol.

What the agents’ work entailed

An agent, also called a shiphusband was a person appointed by the ship-owners. He was responsible for the management of the voyage. For instance he was the person who gathered the investors’ requirements in a legal document and gave instructions to the captain. He made sure that the ship was fit for purpose (repairs, food, wages, distribution of profits etc.) Let me give you an example of the type of instructions owners provided to the Captain through the agent.

Capt James McTaggart, we appoint you commander of our Snow Swift and order you to embrace the first fair wind or good opportunity of sailing with your complement of men being thirty in number directly for the River Bonny on the Coast of Africa and when you arrive there and are safe endeavour to come at the knowledge of what vessels are at Bonny or New Calabar (…)

In other words look out for the competition because the prices of goods may vary. Precise instructions were given regarding the type of goods that needed to be purchased

Proceed to either place where there may be the best opening for trade and then take the cargo loaded on our snow, […] 13726 Bars and open trade with the natives on the best terms you can and Barter the whole of our cargo for as many fine young and healthy full grown negroes men boys and women girls as it will admit off preferring the males though should you find a difficulty in the choice let not sex be your hindrance but pursue your trade with the utmost diligence and purchase also all the elephants teeth you possibly can

Seamen were another category of people involved in the transatlantic. When we think about the transatlantic slave trade, we think about the brutality of crossings. Hundreds of enslaved Africans packed in ships that sometimes have been sailing along the African coast for weeks. We think about the horrors of plantation life, beatings, whips, rapes, torture.

How about Bristol seamen working aboard slave ships?

These were often young men in their early 20s. Some were skilled but more often than not they were employed mainly to look after slaves. So imagine this, young men who have barely left their home. Believing in the promises of a better life. Ending up by choice or sometimes gang-pressed meaning tricked into these ships (through crimping houses: lodgings where sailors were tricked to drink and go with prostitutes. They often couldn’t pay so were forced to enrol and join the navy or slave ships). They were around enslaved Africans who were ready to save their lives by fighting against their captors or desperate enough to jump and drown in the ocean. Life aboard slave ships was hard.

There were great disparities in income between sailors who originated from the countryside and those who belonged to families of sailors. Jonathan Press established that unskilled sailors earned 25 shillings a month (£1 = 20 shillings); a skilled sailor was paid 30 shillings. A carpenter had 70 to 80 shillings (they too were aboard slave ships). Captains could get 80 to 100 shillings. Another important matter was nutrition. It was minimal. Captains could diminish portions for various reasons. Alcoholism was common among sailors working aboard slave ships. They were given alcohol (ale) but in the second half of the century, mostly rum was provided every single day. Alcohol was not just to get them drunk and help them bear their working conditions. It was also used to protect them from disease (scurvy in particular). Those who didn’t drink before the voyage ended up drinking during the crossings. They suffered from malnutrition; dysentery and scurvy were the most common illnesses. Mortality rate was high. Those who survived and managed to come back home were disabled, blind and often as poor as when they left. I said those who managed to come back home. Because, once in the West Indies, enslaved Africans were sold. There was no need for unskilled men aboard. It was also in the West Indies that sailors were paid the 2nd part of their salary. Sailors were given leave of absence of 1 to 3 days knowing that many would have a hard time (especially for those who were alcoholics), getting back to the ship on time. It was easier then to dismiss them sometimes without giving them their full salary because they have broken the term of their contract.

There was another reason why it was better for captains to pay these men in the West Indies.

B.R.O. 08527, November 30th 1788, Answer from the Trustees for the Relief and the Support of Sick and Disabled Seamen, p.160.

6th: The number of men taken on board African and West India ships may vary from local circumstances; but in general, African ships carry about 12 men to 100 tons, in ships of 300 tons burden; And West India ships of the same burden carry about 7 men to 100 tons. (…) No part of the wage of the crew of the African ships is paid in Africa; but on their arrival at the port of delivery or sale in the West Indies, they receive half their wages there due in currency of the island.

Stranded, starving and unskilled sailors were found in the Caribbean in the 18th century. Most of them would work eventually find work in plantations, in the timber industry or move to the American south were they were presented with more opportunities. Abolitionist Reverent Thomas Clarkson managed to convince people of the atrocity of the transatlantic slave trade by telling the story of enslaved Africans but also the stories of poor sailors working aboard slave ship.

B.R.O. 08527, The Following letter treating of the mortality of seamen in the African Trade, was transmitted to the Committee by the Reverend Mr. Clarkson, 1788, pp.136-148.

Your Lordships having requested, that I would make out an account of the seamen lost in the slave trade, I take the first leisure moment that I have been able to find to comply with Your Lordships requests.

(…) It is well known, and can be proved to Your Lordships, that some of the unfortunate seamen are in such an infirmity and debilitated state of health when they arrive in the West Indies, that they are soon carried to the hospital, and die there. Others, to forget their sufferings, and to have a little relaxation after the hardships and severities they have experienced indulge themselves ashore. They drink new Rum, their habit of body is unable to bear it, and they fall victims, I will not say to their intemperance but to the nature of the trade, which has brought them first into a debilitated state and have put them adrift to affect their own cure.

These are men seen in the streets of Jamaica, dying in an ulcerated state, objects both of commiseration and horror. Others, without friends, without money, wonder about in the different islands and beg from door to door, till overpowered by heat, hunger, and fatigue, they fall equally tied, share the fate of their former friends.

Following an act of Parliament in 1747, a Seamen Hospital Fund had been set up. In Bristol, the Society of Merchant Venturers was in charge of the National Insurance Scheme. When they joined a ship, sailors had to sign an article of agreement. A small portion of their wages went to the subscription. However, the insurance company did not systematically pay when sailors came back disabled and in need.

All was not gloomy for seamen. Jonathan press showed that between 1747 and 1789, mortality rate aboard Bristol slave ships went from 18% to 12%. Some skilled workers were sometimes allowed to ask for an advance of salary. They used it to buy goods, such as cloth, sugar, rum, tobacco and then sell these to the rest of the crew during the crossings. Thus making some interesting profits. Because the salary was paid in the Caribbean as I said earlier sailors who had borrow money for these goods had no income by the time they reached the Americas.

Skilled workers could work their way up to the social ladder. However, it took about 25 years for seamen with connections in the elitist circles of Merchants and plantation owners to become captains.

I talked about enslaved Africans as commodities and Labour. I mentioned Rum. Let’s turn to sugar, the most important source of wealth that came from Bristol plantation owners and merchants. Sugar made the Britain rich. Before being turned into sugar, molasse was produced by slaves.

Molasse was put in barrels and sent to Bristol where it was cleaned, treated and turned into crystal sugar. Sugar refinery used complex and expensive machines (boilers, furnaces, water pumps etc.). Robert Aldworth invested in the business and established the first sugar refinery in 1612. He later got a partner, his son-in-law Giles Elbridge. Together they developed that trade. Aldworth later became president of the merchant venturers. Donald Jones showed that between 1728 and 1785, the import of barrels of molasses or muscovado as it was also called went up (from 13 600 to nearly 23 000). The number of people involved in that industry however decreased. In other words, the industry of sugar refinery was in the hand of an elite group that was reluctant to share privileges. As time went by, many refineries closed their doors because it was lucrative but risky business. Fire among other things plagued that industry. A fire brigade paid by local authority was finally set up in 1837. Until then safety issues had been the owners responsibility.

However, that industry created a new category of businessmen. Onesiphorus Tyndall and Isaac Elton are only a few of well-known names in the industry. Tyndall and Elton set up the Old Bank in 1750. Henry Bright and Jeremiah Ames created the Hardford Bank at the same period. Sugar industry also required new skilled workers. Sugar boilers were needed. It even became a craft. I looked at the will William Price, a sugar boiler who was able to make a decent living in that booming industry. He helped his two sons get into shoe making industry (he paid for their apprenticeship). Being apprentices in the sugar industry was probably too costly for price. Price did not become a rich merchant but by the time he died he in 1769, he was able to leave a generous sum to his sons.

Merchants invested in sugar but also in tobacco, another important commodity that used slave labour.

Was all that wealth so important that those involved in the trade forgot that it was the source of suffering for slaves?

Madge Dresser and Sue Giles showed that some owners did not feel confortable with that trade.

John Pinney, slave trader and plantation owner from Bristol declared “I was shock’d at the first appearance of human flesh for sale. But surely God ordain’d ‘em for the use and benefit of us: otherwise his Divine will would have been made manifest by some particular sign or token”.

Here is a comment from the Bristol Gazette’s Reader in 1788; I am shocked at the purchase of slaves…I pity them greatly, but I must be mum, for how could we do without sugar and rum? Especially sugar, so needful. What, give up our dessert, our coffee and tea?

The abolitionist movement in Bristol

Bristol did take part in the anti-slavery movement that swept across the kingdom.

Religion influenced the abolitionist movement in Bristol through the story of John Wesley. Wesley was born in Lincolnshire. He studied at Oxford. He travelled to Georgia on an evangelical mission. That is where he met Moravian missionaries, who originated from Saxony. According to Kenneth Morgan, they greatly influenced Wesley’s views on religion and on salvation in particular. Wesley came back and started teaching in Bristol and its surrounding areas, Kingswood in particular. His meeting took place after other religious services to avoid competing with other religious denominations. Quakers, Presbyterians and other groups regularly attended Wesley’s service. He advocated open air preaching and the centre of Bristol seemed to be an adequate setting. The great majority of Wesley’s followers were miners or people of humble origins living in Kingswood or nearby. These faithful followers trusted him. He would pay a visit to several individuals. He opened a school for boys there. The most humble part of the population was attracted to Arminian principles advocated by Wesley. Methodist Calvinists believed in pre-destination. Only a few people were to be saved. Arminian Methodists on the other hand believed in conditional predestination. Strong faith was the key to salvation. Followers were allowed to express their fervour publicly. Authorities in Bristol did not like all that noise (speaking in tongue, crying publicly etc.). Wesley was forbidden to preach in Bristol on several occasions. He published a pamphlet Thoughts on Slavery in 1770. He advocated a fairer treatment of slaves in plantations. Wesley was among those who argued that unsaved Africans also had an immortal soul just like Europeans. This may not seem incredible but at the time when most people believed that Africans were the descendants of Ham (He saw his father’s drunk and naked, he did not do anything whereas Noah’s other sons: Shem and Japheth covered Noah) and were therefore rightly doomed to be slaves, Wesley’s idea was ground breaking.

Wesley was not the only one involved in the abolitionist movement in Bristol at the time. The Quakers represented a wealthy category of people they too were involved in the abolitionist movement. Peter Marshall demonstrated how The Society of Friends or Quakers would refuse to work with people directly involved in the slave trade.

A few individuals were also active in the abolitionist movement. A surgeon Dr John Bishop Estlin and his daughter Mary supported the movement in various ways. The Estlin papers held at BRO are of great interest. The Estlins organized talks in Britain. They involved former slaves who had managed to escape to Canada. Estlin and his daughter promoted these tours. They were in contact with powerful members of the Underground Railroad, a secret network of American abolitionist that expanded to Canada. Mary Estlin produced drawings that she sold to raise money to support the movement.

There are also interesting cases or rather individuals who couldn’t quite decide where they stood on the matter. George Daubeny was the mayor of Bristol, a powerful man who signed petitions against slavery. However under the pressure of Merchants he decided to join pro-slavery campaigners in 1786.

Another interesting case involved Wilberforce and Kimber. In 1792 MP and abolitionist William Wilberforce decided to show people how brutal the slave trade was. He chose 3 vessels. One of them was a Bristol slave ship called the Recovery. Wilberforce accused the captain, John Kimber of having tortured a young slave who later died from her injuries. Kimber was arrested and tried. He was acquitted. Details of the trial appeared in many papers throughout the country. Bristol newspaper, The Felix Farley covered the event extensively. This trial marked a turning point in Wilberforce’s career. After being released, Kimber demanded a public apology from Wilberforce as well as £5000 compensation. Wilberforce refused to pay. Kimber started harassing him. He even went to Wilberforce’s home. Wilberforce’s allies Lord Rokeby and Lord Muncaster turned to Lord Sheffield an MP representing Bristol. They asked him to intervene. He did and Kimber stopped.

The slave trade was abolished in 1807 but slavery continued in the West Indies. Another campaign started and eventually led to the abolition of slavery in 1833. In Bristol a few cases caught people’s attention. The Huggins case for instance. Ed Huggins was a slave owner from Nevis. He was accused of having broken the law.

British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (B.E.C.M.), 1996/24/1290, Correspondence relating to punishments inflicted on certain Negro slaves in the Island of Nevis, and to the prosecutions in consequences.

Nevis at a meeting of the Gentlemen of the Assembly on Wednesday, the 31st day of January 1810, […] Resolved, that it is the opinion of this House, that the conduct of Ed Huggins was cruel and illegal, […] inflicted punishment on his negroes in the public-market place of his town. 242 and 291 lashes were given, and lashes counted aloud by John Burke. Were present: Ed Huggins; Dr. Cassin; Peter Butler and others. Flogged by two expert whippers according to witnesses.

Newspapers covered the story extensively. Ed Huggins was tried and acquitted despite the fact that he had broken the law. It was against the law to to add humiliation to punishment by whipping slaves in public. A Reader expressed their opinion on the matter. Here is an example

British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (B.E.C.M.), 1996/24/1290. Published in the St. Christopher Gazette 24th August 1810.

Sir, Coming from a country where the fountains of justice still remain pure, and the liberty of the press is respected, Your Excellence must have experience the same feeling of surprise and indignation which the respectable part of this community did on hearing a verdict of acquittal pronounced against one of the actors of that bloody scene. […] had they all died, the act by which they suffered being according to the declaration of the jury a legal act, the authors of it would have been perfectly guiltyless.

Pro slavery campaigners were also very active. Henry Bright, several times mayor of Bristol, slave traders and plantation owner wrote a pamphlet in 1833 right before abolition.

B.R.O. 11168/73 (a), printed pamphlet by Henry Bright, Bristol, 1833.

[…] We have noticed none of the schemes for emancipation because we look at them all as perfectly chimerical. Continuous labour, or labour to be commanded at all times, is necessary to the agriculture and manufactures of the colonies. We are confident it cannot be sacred under any plan yet hinted at. We have humanely and in a pecuniary sense, considerable administered a system approved and enjoined upon us by our country; and we shall demand from the people of England, who became rich by the profits and participated in the guilt (if guilt there be), a full, fair, and immediate compensation for our slaves, and the most ample pecuniary security and political protection for our lands, should they compel us to adopt any alterations in the system injurious to our property.

Emancipation was not chimerical. An act of Parliament granted it. However, Bright and others did receive compensation for the loss of their property i.e. slaves. British slave owners received £20 million (some estimates say that it is the equivalent of £1.8 billion in todays money). An interesting research is being conducted at the moment at UCL led by Catherine Hall, and it looks at where, out of the £20 millions, the £10 million that stayed in Britain went. Bristol slave owners are said to have received £500 000. Madge Dresser thorough analysed where some of that money went. She looked in particular at the cultural and social impact the slave trade had on Bristol. Merchants turned to philanthropy and education. Bristol continued to prosper for a few years in the 19th century. Merchants turned to other trading ventures such as the railway.

The story of Bristol continues …

See also: Bath and the Slave Trade