Intellectual life in Edinburgh

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- The Encyclopaedia Britannica, a major production of Enlightenment Scotland

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh

- George Heriot’s School

- George Heriot’s School (originally ’hospital’) was founded in the early 17th century by George Heriot, the King’s jeweller, for poor orphans.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The University of Edinburgh

- The University of Edinburgh

- The present-day University buildings (early 19th c.), by Playfair who also designed the Royal Circus and the Royal Institution.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, whereas the university of Glasgow, founded in 1451 under James VI of Scotland, aroused the admiration of many foreign travellers for its noble architecture, the university of Edinburgh, built in 1583 under James VI of Scotland and Ist of England, shocked the aesthetes with the mixture of styles of its construction and the disorderly layout of its buildings.

Academic studies then lasted four years and the different disciplines were taught by just eight teachers: a professor of theology, a professor of oriental languages, a professor of mathematics, four professors of philosophy and a professor of philology and Arts. The university was the target of much criticism: its syllabus was deemed to be too heavy and obsolete, the recruiting of its professors too arbitrary and the dilettantism of some of them was severely denounced. Most professors were in fact appointed to their chairs by the town councillors and very often the election of candidates depended more on their political connections than on their diplomas and personal merit.

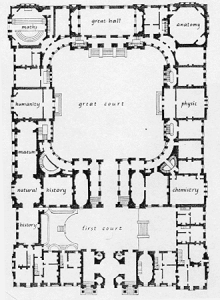

- Map of the University

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

George Drummond (1687-1766), six times Lord Provost of Edinburgh between 1725 and 1764, wanted to put an end in 1759 to these secret schemes which were rampant in the faculties, particularly within the Faculty of Medicine, and which were greatly detrimental to the prestige of the Alma Mater : “Provost Drummond, who had long presided in the Town Council (the patrons of the university),” relates Thomas Somerville in My Own Life and Times, 1741-1814 (Edinburgh, 1861) “[decided] that the welfare of the city and university, and also of the country at large, might be greatly promoted by due care being taken in the appointments to the Medical chairs, which, he proposed, should thenceforth be invariably filled by the fittest men, irrespectively of personal influence” (22).Even if the intra-muros intrigues had not totally disappeared by the end of the eighteenth century, the professorial body was nevertheless well-represented in Edinburgh in 1801 and clearly justified the high prestige enjoyed at that time by this Scottish university all over Europe. Since 1760 teaching had been diversified and several professorships had been created: “Rhetoric and Belles Lettres” (1760), “History” (1767), “Materia Medica” (1768), “Surgery” (1777), “Astronomy” (1786) and “Agriculture” (1790). This enrichment of the syllabus satisfied a genuine need for revival in a country undergoing a complete economic and cultural evolution.

- The University of Edinburgh

- Bough, Snowballing, the University

(National Galleries of Scotland)

The University’s new buildings by Robert Adam and Playfair can be seen to the left.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

After 1770 the number of students continued to grow. In 1789, the year when the foundation stone of the new university built to the design of the famous architect Robert Adam ( 1728-1792) was laid, the Alma Mater was at the peak of its fame.

The traveller Alexander Campbell declares in the second volume of his book A Journey from Edinburgh through Parts of North Britain (1802; rpt. London, 1811):

“The university of Edinburgh was in the most flourishing condition. Upwards of a thousand young men, from almost every nation in Europe, and most of the United States of America, were prosecuting their studies at this celebrated seat of education” (251).

- Documents about lectures

- Alexander Campbell, A Journey from Edinburgh through Parts of North Britain, vol. 2

(1802; rpt. London: John Stockdale, 1811) 254-55.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Documents about lectures

- Alexander Campbell, A Journey from Edinburgh through Parts of North Britain, vol. 2

(1802; rpt. London: John Stockdale, 1811) 254-55.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Documents concerning the lectures of some of these professors have survived, in Anatomy and in Philosophy and Greek Literature

Some of them were friends with builders and painters such as the Nasmyth family; some took part in the religious controversies.

They are also mentioned by one of Smollett’s characters.

- Monro’s book on Anatomy

- David Bayne Horn, A Short History of the University of Edinburgh 1556-1889 (Edinburgh UP,1967)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- A decorated capital from notes showing a regent lecturing in anatomy

- David Bayne Horn, A Short History of the University of Edinburgh 1556-1889 (Edinburgh UP,1967)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Philosophy and Greek Literature

- Classcards for 1787 lectures

- Andrew Dalzel’s course on Greek and Dugald Stewart’s course on Moral Philosophy

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The Athens of the North

Edinburgh was known as “The Athens of the North” because of its brilliant intellectual life, due to the presence of major philosophers of the “Scottish Enlightenment” such as the theorist of empiricism, David Hume, the moral philosopher Adam Smith, and the writer on aesthetics Dugald Stewart.

In Smollet’s novel Humphry Clinker, Matthew Bramble called Edinburgh ’a hotbed of genius.’

The ’Scottish Enlightenment’ first developed in the Old Town.

Here I stand at what is called the Cross of Edinburgh, and can, in a few minutes take fifty men of genius and learning by the hand.

Thomas Pennant, 1769

It was partly to have a setting in keeping with its status as the new Athens that in the later Georgian era Edinburgh became a city of neoclassical architecture in the New Town:

I charge you no to think of settling in London till you have first seen our New Town which exceeds anything you have seen in any part of the world

David Hume, May 1771, writing from his new house in St Andrew’s Square

- The monument of David Hume

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The monument of David Hume by Robert Adam (1777), in Calton Old Burial Ground, on a hill to the East of the New Town.

It is a cylinder - a geometrical shape - because of the philosopher’s materialistic convictions.

- The obelisk

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

The obelisk erected in 1844 is a memorial to the “1793 Martyrs”, radicals who were prosecuted because of their sympathies for the French Revolution.