Medicine in Edinburgh

Illnesses and medicine in Scotland: First half of the 18th century

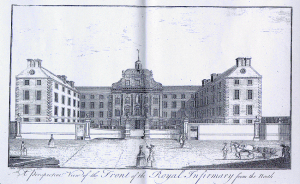

- A perspective view of the Front of the Royal Infirmary from the North

- The Infirmary is mentioned by Smollett’s character Matthew Bramble

Concerts were given on behalf of the Infirmary

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The insalubrity of Scottish towns bred the worst illnesses. In the space of two years (1740-42) 2700 people, above all children, died of smallpox in the town of Edinburgh alone. The devastation caused by the plague during the terrible years of 1644-48 were still to be feared, if the population did not take the necessary precautions in hygiene.

At the start of the century, medicine had made very little progress. The number of doctors was still insufficient and their competence more or less doubtful. For example, the way to cure a cold recommended by the famous Edinburgh doctor, Doctor Clark, was the following:

Doctor Clark’s directions to Sir Robert Gordon’s son. Edinburgh, May 20, 1739 - Give him, twice a day, the juice of twenty slettars, squeezed through a muslin rag, in whey : to be continued while he has any remains of the cough..

Such was the miracle remedy of the renowned Doctor Clark according to E. Dunbar Dunbar, author of Social Life in Former Days, 1620-1770 (Edinburgh, 1866), 145. In reality, many people, either from the town or the country, did not even bother to consult a doctor and resorted to traditional remedies for treatment, like those recommended by John Hope in his very serious work:

To preserve earth worms, the largest and fattest enough ought to be split up, well washed, and then dried....They are nourishing and antacid ... and commended inwardly in the jaundice, dropsy, colic, spasms, convulsions, apoplexy, palsy, scurvy, rheumatism, gout, gravel , worms. (II, 508).

An infusion of Sheep’s dung is given in the small pox ; of Horse-dung in the Rheumatism, of Peacock-dung in the Epilepsy. (Lectures on the Materia Medica, Edinburgh, 1770, :III, 551)

- Royal College of Physicians

- (demolished in the mid 19th century)

coll. The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

This is the design at James Craig’s feet in his portrait

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

It is not surprising that such medicine did not always obtain the desired recoveries! In Edinburgh, people of condition, with failing health, went for cures in the spa towns of Moffat or in the Highlands, where the pure mountain air and goat’s milk strengthened their delicate constitutions. The less well off, orphans and the aged could hope to find some relief for their aches and pains in the rare hospitals of the country (George Heriot in Edinburgh, John Cowane in Stirling, George and Thomas Hutcheson in Glasgow) but these establishments did not have highly qualified staff and they were more charity houses than genuine medical centres.

Medicine, therefore, needed to make enormous progress to catch up and to combat the numerous illnesses caused by the lack of hygiene in general, by overpopulation conducive to contamination and by the overwhelming misery, which gave rise to so much affliction for Scottish people.

slettar (Scots): wood-louse