Painters and painting

Education

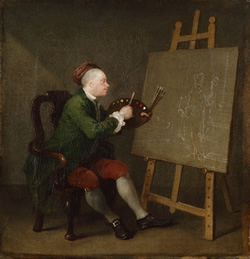

- Hogarth, Self-Portrait painting the Comic Muse

- (1757, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

Hogarth is at his easel, holding a palette showing the traditional arrangement of colours (brighter colours first near the thumb), with several brushes kept as reserve since at the moment he is working with a palette knife.

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

In the first half of the century, young painters learned their art in workshops under the guidance of an experienced painter. Among them was St Martin’s Lane Academy, run by the painter Hogarth, founded in 1735

In 1768, a group of painters decided to form the Royal Academy, in imitation of the Italian academies of the Renaissance, and of the French Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture founded in the 17th century. The first President of the Royal Academy was Sir Joshua Reynolds.

A large part of the training consisted in teaching young painters how to paint historical scenes, including scenes from Antiquity with warriors who by convention were represented as nudes, or mythological figures; so that painting from a male nude model was one of the main exercises known as the ’life class’ (=painting ’from life’), as shown in Zoffany’s painting (1771-72) reproduced on the Academy’s webpage on its history (mentioned above). They would also learn to draw from casts of antique sculptures, which appear on the shelf behind the members.

The major genres:

Portrait painting was widely pracised by famous painters, since family portraits (sometimes lifesize) would be placed in favourable positions in the major rooms of houses to welcome and impress the visitors - see the drawing room of the Georgian House in Edinburgh with a portrait above the fireplace

- the drawing room of the Georgian House in Edinburgh

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Painters would have the sitter come for a sitting to paint the face from life (NB : the word ‘sitter’ is used even if the person represented is in another position, for instance standing.) For the rest of the body, the painters would use a ‘lay figure’ – a wooden articulated manikin (about 40 or 50 cm) that they would put in different positions; they would also have lay figures for horses. These remained in use in the 19th and 20th centuries and you still find some with suppliers of artists’ materials, for human figures or for horses.

A ‘sitter’ should not be confused with a ‘model’: a sitter commissions his or her portrait from the painter, and is identified – ‘Portrait of Commodore Keppel’ (1752, now National Maritime Museum at Greenwich)…, ‘Portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire’ (1784, still in the family at Chatsworth) … both by Reynolds ; a model makes a living by sitting for painters as an anonymous figure in the painting.

Portraits followed certain practices. The sitter would assume a pose in which the head, arms and legs would be balanced in opposite directions, to give a more lifelike appearance, this is known by the Italian term contrapposto. Standing sitters placed against a landscape background would have their heads above the horizon line; since the horizon line is by definition at the height of the viewer’s eyes, the sitters would thus be in a superior position with their heads above those of the intended viewers.

See for instance Captain Robert Orme (1756, now National Gallery) and Lady Bampfylde (1776, now Tate Gallery), both by Reynolds.

The poses of portraits frequently imitated well-known motifs from ancient or Renaissance art: the attitude of Lady Bampfylde is borrowed from the ancient statue of Venus in the Medici collections, and that of Captain Orme from a rider in a fresco in the Florentine church of Ognissanti from which Reynolds had taken a drawing.

Cities frequented by the fashionable society, such as Bath, would have painters staying there to make portraits of the visitors, such as Gainsborough: the double portrait of Commodore and Lady Howe was painted when they were visiting Bath (1764, the portrait of Lady Howe is now at Kenwood, the portrait of Commodore Howe is still in the family collection)

Painters would also evoke city life by making portraits of writers and actors: Garrick, by Hogarth (1757, Royal Collection), by Gainsborough (1770), and by Reynolds (1773, both National Portrait Gallery) or of musicians : the Linleys at Bath by Gainsborough, 1770 Victoria and Albert Museum).

Landscapes: the word was still felt as a Dutch word and sometimes spelt ‘lantskip’, because of the influence of Dutch landscape painters of the 17th century; the Italian word ‘paese’ (plural ‘paesi’) was still sometimes used. Landscapes were linked to topographical representation, and idealised it following the practice of ‘Classical’ landscape paintings, the Italian views of Poussin and Claude (‘Claude’ is the English name for Claude Lorrain). Space in a landscape painting was subdivided in depth into three areas: the ‘foreground’ in clear outlines of a brownish colour with framing trees on both sides, the ‘middle distance’ in green with meadows, small buildings and usually an expanse of water (a lake or a river with a bridge), and the ‘distance’ with blurred hazy bluish hills. Such effects of changing colours and gradually decreasing clarity of lines, known as ‘aerial perspective’, were meant to render the sense of depth.

- the dining room of N°1 Royal Crescent

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Such views decorate townhouses or country houses, and offer painted vistas between windows or opposite them (see the dining room of N°1 Royal Crescent).

One of the major landscape painters was Gainsborough, who practised rough brushwork to suggest trees in the wind (The Market Cart, 1786, National Gallery) or waves.

He also used bridges in the middle distance together with mellow colours to link the various parts of the painting in a poetic atmosphere (The Bridge, 1783, Tate Gallery).

Conversation pieces and scenes

‘’Conversation pieces’’, scenes representing a family in a domestic setting, were frequently commissioned from painters (see the family depicted by Highmore, 1744, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum).

A variant which developed in industrial towns was that of a group of observers watching a scientific experiment: Wright of Derby, The Orrery (1766, Derby Museum and Art Gallery).

Techniques:

’Linear perspective’ - especially important in townscapes: the rules of geometrical projection of a three-dimensional landscape on to the flat surface of a painting so that it renders the sense of depth. It was developed in the Italian Renaissance, and young artists were trained in it. Georgian painters used it to represent the vistas of streets : the lines of houses converging towards a vanishing point, the choice of the the viewer’s ’point of view’ in the literal sense of the term (opposite the vanishing point), which may represent a moral ‘point of view’ - such were the major perspective techniques.

- Hanover Square in London (1788)

- Hanover Square in London (1788) by Dayes

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Townscapes, within that geometrical framework, emphasized the regularity of the architecture.

The view of Hanover Square in London (1788) by Dayes is a good example.

Hogarth made fun of those who were unable to master the rules of perspective in his frontispiece for a 1754 handbook, showing the errors in the structuring of space that a skilled painter had to avoid, such as people standing on the foreground pavement or at the window in a house seeming close to the river in the middle distance or to other people in the background.

Most colours were of natural origin, such as ochre, the oldest pigment, or the red earths: they are the predominant colours in numerous paintings, with various shades used to model the forms. Chemical pigments, which were largely developed later (19th century), were for some of them first invented in the 18th century, in particular ’Prussian blue’ (named because of the Prussian chemist that discovered it) which allowed painters to paint bright blue-green skies. When looking at the overall effect of a painting, we should take into account the range of colours used in each period - as a contrast, look at the vivid chemical colours of 19th century painting. Conversely, in the 18th century, the desired effect was that of variations within harmonious colours. For instance, look at the shades of ochre and brown used in landscapes to model the outlines of hillocks and rocks, or in townscapes at the various red ochre shades suggesting the different façades of houses: William Marlow Old London Bridge (1762, Museum of London).

- Old London Bridge (1762, Museum of London)

- Old London Bridge (1762, Museum of London) by William Marlow

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

How to relate colours: warm colours (red and yellow and their variations) were supposed to give the impression of coming forward, so they were used for the main figures, whereas blue was supposed to recede and thus to be appropriate for the background.

Pigments were kept in bladders, and they had to be prepared just before painting as they did not keep a long time. Metal tubes were invented in the 19th century, and they kept the paint a long time, so that painters were enabled to travel and paint in the open air. Earlier, painters took a notebook and chalks with them to make preparatory drawings of a landscape on the spot, and they painted the final landscape in their studio - usually a composite landscape containing elements from different drawings made in different parts of the scenery.

Paintings would be made up of several successive layers of paint, with days or weeks between them to allow them to dry before the next one. The most traditional technique was to have the first ones ‘laying in’ the main outlines, and the last ones adding the ‘finishing touches’ in great detail. Some painters preferred a bolder brushwork, by working ‘alla prima’ (putting in the last layers of paint when the previous ones were not yet dry so that they could fuse), or by leaving details rough - ‘unfinished’ - instead of giving them a high finish, to confer on them the impression of movement, as in Gainsborough’s portraits, but this was not always appreciated by the sitters - he quarelled with the husband of one of his sitters who complained that such rough treatment was not up to the beauty of his wife.

Tools: Painters would use optical tools to help them with perspective

For landscapes, Gainsborough used a showbox now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in which he would put painted transparencies representing landcapes, with candles behind them so that he would experiment on the light effects he would use in his paintings.

Engraving

Engraving was a widespread form of art; prints publicized views of city life such a Hogarth’s series. Hogarth obtained that prints should be protected against plagiarism by a copyright law (1735) so that engravers could live from their activities.

Decorative painting

Painters would be called upon to provide motifs and drawings for various decorative arts: signboards (see Hogarth’s views of streets with trades showing the signboard hanging in front).

They would also provide drawings to be reproduced on domestic objects, such as porcelain plates or vases – in the Wedgwood pottery manufactory, ‘pattern books’ were available to reproduce motifs. The views shown on engravings would thus be disseminated to the public and to distant patrons as decoration on objects of daily life or meant for display: for the dinner service ordered by the Empress Catherine of Russia Wedgwood had to comply with her wishes to have views of numerous places in Britain, especially Gothic buildings and parks: this was the image of Enlightenment Britain that other sovereigns wished to imitate. The service of more than 600 pieces (900 originally) had a different view on each; they were taken from several collections of engravings previously published to meet the public demand for views of the country, made by artists who travelled through the provinces to take drawings. They showed castles, parks, city scenes such as the newly-built Westminster Bridge, and industrial scenes such as canals or the foundry at Coalbrookdale; they were chosen to be adapted to the shapes of the dinner pieces on which they were placed, fairly flat motifs with a round frame for plates, or elongated views for oval dishes, but curved arrangements for dish covers with a handle.

Where could the public see paintings?

There was no public picture gallery - the National Gallery in London dates from 1824, the National Gallery of Scotland from 1859; the British Museum, opened in 1759, mostly contained other types of exhibits (natural curiosities, coins, books). Paintings were largely in private collections, where guests would view them; such collections were in country houses or townhouses, and some painters such as Reynolds could form their own collection of works by the ‘old masters’ (Rubens or Rembrandt) that they admired and used as models.

Paintings would also be viewed at auctions, which served as exhibition rooms. Christie’s auction house opened in 1766 in Pall Mall; in 1823 it moved to its present premises in King Street.

The Royal Academy in London (see above ‘Education’, from 1768) had, and still has, an annual exhibition of paintings by its members and associates. It was sometimes an occasion of disputes between the painters and the governing body of the Academy, when the ’hanging committee’ had positioned a painter’s work in an unfavourable light: painters were very careful about the direction of light on their portraits or townscapes so that it would throw the forms into relief.

Paintings were also known to the public through engravings, which were a frequent decoration in households: the visual culture of a large part of the population was in black and white.