Canals

- Canals (1760-1780)

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Navigable waterways

They consist of rivers, rivers artificially made navigable, and entirely man-made canals frequently named ’cuts’ in the 18th century.

Making rivers navigable had started in the Renaissance; in the Netherlands, the 17th century was a great canal age. In early 18th century Britain, in areas which were soon to have a canal network, some rivers were made navigable: the Aire (from the North Sea) as far as Leeds in the first decade of the century, and the Mersey and Irwell around Manchester in the 1730s.

In the mid 18th century, before the canal age, the navigable waterways numbered some 1000 miles; a century later, at the end of the canal age, overtaken by rail, there were more than 4000 miles.

First canals

The first canals were built in the NW, around 1760.

The Bridgewater canal, built by the Duke of Bridgewater (who had been inspired by the ’Canal du Languedoc’ - ’Canal des Deux Mers’ or ’du Midi’ - while on his Grand Tour), to bring coal from his mines at Worsley to Manchester, later extended to the river Mersey in order to reach Liverpool (a harbour); the price of coal was halved, and industry prospered in Manchester.

The first stages of the ’Grand Cross’, planned by James Brindley (the engineer of the Bridgewater canal) to link the seas NE, NW, SE, SW:

- the Trent and Mersey canal linked the NW (the Mersey and the Bridgewater canal, Manchester and the harbour of Liverpool opening the Atlantic routes) to the NE (the river Trent and the harbour town of Hull opening towards the North sea), through the Potteries.

- the Staffordshire and Worcester canal linking the Trent and Mersey Canal to the Severn, reaching it in the new town of Stourport, and leading to the SW and the harbour town of Bristol.

The first stages of the Leeds and Liverpool canal, connected at Leeds with the river Aire which flows into the Humber and leads to Hull on the East coast

In Scotland, the Forth and Clyde canal, joining the Firth of Forth upstream from Edinburgh and the Clyde downstream from Glasgow, was started

Supporting and financing the canals

The first canals:

- the Bridgewater canal was designed at the command of the Duke and financed by his personal fortune

- the construction of the Trent and Mersey canal was initiated by Earl Gower, a Staffordshire landlord, brother-in-law of the Duke of Bridgewater (the Gower family was also allied by marriage to the Dukes of Bedford, hence Gower Street in the Bedford Estates in London, showing the interaction between developments in provincial transport and in London town design; Bridgewater’s mother also came from the family of the Dukes of Bedford); Josiah Wedgwood influenced the planning so as to have the canal cross the Potteries. The Birmingham industrialist Boulton was also on the management of the canal; Bridgewater’s agent Gilbert had been an apprentice in the Boulton works.

After the Bridgewater canal, canals were financed by companies, with shareholders and loans; when the canal was finished, the companies charged the barges to raise money for the upkeep of the canals.

Acts of Parliament were obtained to authorise the construction of each canal.

- Export: the canals exported the products of the industrial Midlands.

- Import: the canals imported the raw materials used by the industries, and the goods needed by the large population of these areas.

- Transport: horse-drawn waggons on rails were used to carry goods to the barges, tipping them into the boats (coal), or equipped with waggon bodies that could be lifted with their contents into the boats

- Passenger traffic: the Bridgewater canal, from 1767, carried passengers from Manchester to Altrincham downstream, and then in eight hours from Manchester to Runcorn near the estuary; from 1800 there was a passenger service from Edinburgh to Glasgow, at 8 miles/hour.

Second phase

To see the later extension of the canal network, roll over or click on the image.

Some of the canals started previously in the North to link the Liverpool-Manchester area in the West to the Eastern counties and the North Sea were completed:

- the Rochdale canal,

- the Leeds and Liverpool canal flowing into the Aire at Leeds

New canals were dug linking the existing network to the SE and London:

- the Kennet and Avon canal linking the Avon (Bristol area, towards the Atlantic) to an affluent of the Thames, the Kennet

- several canals linking the Trent and Mersey canal to the Thames, completing the ’Grand Cross’:

- the Oxford canal, reaching the Thames at Oxford

- the Grand Junction (later called Grand Union), reaching the Thames closer to London

- the Regent’s canal linking the Grand Junction to a point on the Thames downstream from London near the area where docks developed (Limehouse)

- canals in the Birmingham area linking it to the Grand Cross (see detailed map on the Birmingham page)

In Scotland, canals were constructed to avoid sailing round the dangerous coasts of the North of Scotland:

- the Forth and Clyde canal was completed (1768-90)

- the Caledonian canal joining natural lochs was built (1803-22)

Engineering

- Bridgewater canal

- Engraving by Pollard, 1794

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The canals were feats of engineering. The first engineers were those skilled in draining; they plotted and surveyed the land. They had to provide a level waterway in spite of the rise and fall of the land, with the choice of

- either finding means of crossing valleys and hills in order to take a direct route,

- or taking a circuitous route to avoid irregular terrain (’contour canals’).

For the Bridgewater canal, the engineer Brindley carried the canal over an aqueduct to cross the Irwell.

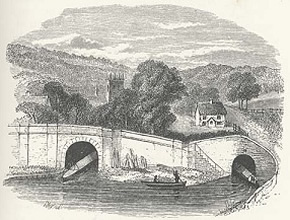

- Trent and Mersey canal

- The canal to the right is Brindley’s, from Smiles’s Lives of the Engineers (1864)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

For the Trent and Mersey canal, he dug the longest tunnel then in existence, near Stoke-on-Trent, the Harecastle tunnel: it was impossible to follow the contours because going uphill would have meant having a supply of water on top and there was no such possibility.

The canals in the North linking the West and East coasts had to cross the Pennine range, for which two solutions were used:

- the Rochdale canal ascends and descends the slopes with locks, which led to the construction of numerous reservoirs along the route to maintain a supply of water for the locks

- the Leeds and Liverpool canal takes a longer course to follow the contours of the land wherever possible, and only where impossible has grouped staircases of successive locks.

- Grand Junction canal

- The lock at Stoke Bruerne; the last house on the right bank in the middle of the photo is now the Canal Museum

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Grand Junction canal

- The Blisworth tunnel on the Grand Junction canal

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

The canals linking the Midlands to the Thames were either:

- a contour canal, the Oxford Canal, avoiding slopes and following a circuitous route dependent on the terrain contours,

- a canal with engineering works, tunnels and locks: the later Grand Junction Canal constructed on a shorter route by Jessop. At its Northern end, where it joined the Oxford Canal, locks and reservoirs with pumps had to be built to preseve their different water levels.

- KirkstallLock

- engraving (1827) after Turner’s KirkstallLock on the RiverAire

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Exercises

Read the biography of Brindley (1864) by Samuel Smiles, the 19th-century author of Lives of the Engineers, written when Victorian Britain was creating a retrospective image of the industrial pioneers.

- Kirkstall lock

- The bridge over the canal from Turner’s viewing point above the canal; the arch of the bridge is visible behind the tree trunks, the tower of the abbey is between the branches

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Kirkstall lock

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Let us study how canals were represented by artists - an issue raised at the National Gallery Exhibition ’Turner Inspired: In the Light of Claude’ (2012).

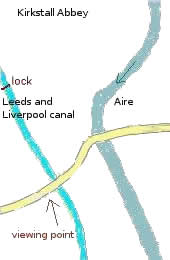

In space: the relation between image and reality is controversial; see the debates on the exact place represented in Turner’s painting Kirkstall Lock on the RiverAire (1824-25, Tate Gallery) - the river Aire as mentioned in the title, or the nearby canal?

- an interpretation following the approach of ’cultural geography’ by Stephen Daniels (1992), arguing that the title is meant to preserve the associative power of the river’s name

- an identification by Joseph Black, a Professor of Engineering at Bristol (late 1990s)

- a study of the sketchbooks and paintings by David Hill, a Professor of Fine Art at Leeds (2009)

- Kirkstall lock present-days views of the site (about 3 miles W of Leeds)

- The view from the Aire bridge showing the tower of the abbey

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Kirkstall lock present-days views of the site (about 3 miles W of Leeds)

- The view from the bridge over the canal towards the lock

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- a query by a member of the Tate Gallery to local people, with a reply including a map and arguing that the viewing point was above the canal (2009).

In time, from plan to retrospect - an example from the Leeds and Liverpool canal - rollover the image.

Simulation of engineers’ choices

Another role-playing exercise has been authored by historians of Birmingham, concerning a different branch of engineering: engine manufacture.