Hospitals in London

The word “hospital” applied to charitable institutions for children and paupers as well as to houses for the sick which were also frequently called “Infirmaries”. Among the hospitals in Britain were those of London:

The Foundling Hospital

The Foundling Hospital was founded by Thomas Coram in 1739

- Captain Thomas Coram

- William Hogarth, portrait of his friend Captain Thomas Coram, the founder of the Foundling Hospital

(1739, Foundling Museum/ Bridgeman Art Library)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

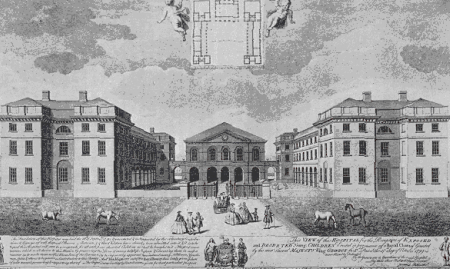

The Foundling Hospital was the most famous charitable institution in London. It was opened in 1741 thanks to the efforts of Captain Thomas Coram (c.1668?1751), a retired sea captain. From 1729 he had campaigned tirelessly in order to obtain a Royal Charter for the Institution, and had skilfully managed to obtain the moral and financial support of major aristocratic families and City merchants. From 1745 the Hospital was housed in a new edifice designed by Theodore Jacobsen and erected in the middle of fields, on the northern periphery of the built up area of Bloomsbury.

The early regulations of the Hospital specified the conditions of entry of infants:

“No child exceeding the age of two months will be taken in, nor such as have the evil, leprosy, or disease of the like nature, whereby the health of the other children may be endangered; for the discovery whereof every child is to be inspected as soon as it is brought, and the person who brings it is to come in at the outward door and ring a bell at the inward door, and not go away until the child is returned or notice given of its reception; but no questions whatever will be asked of any person who brings a child”.

One major problem in the early years of the Foundling Hospital was the excessively large number of applicants wishing to leave infants to its care. Some babies were put out to nurse, others sent to subsidiary hospitals in the country, others were simply refused. The mortality rate among the inmates was also very high, although the children were well looked after. As soon as they were old enough, the surviving foundlings were set to work-the girls making and mending linen, the boys making hemp and nets (in open-air galleries). Later many were apprenticed as servants, while some boys were sent out to sea.

In order to attract rich visitors and sponsors, the Foundling Hospital soon exhibited in some of its rooms paintings and sculpture donated by leading artists of the day, such as Hogarth, Hayman, Highmore and Rysbrack. Handel, the major composer of the day in London, also contributed to the charity by regularly directing his ’Messiah’ in the chapel of the Hospital in the 1750s. The institution survives to this day, but was moved to the suburbs of London in 1928. The site of the Hospital is now occupied by playing-fields, but the Court Room and the galleries exhibiting the works of art donated in the 18th century were reconstructed nearby in Brunswick Square, where they may be visited.

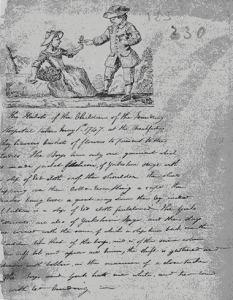

- Sketch of a Foundling Boy and Girl, I May 1747

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Admission of Children to the Foundling Hospital, 1749

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The Girl’s Dining Room

- by John Sanders (1768-1826)

watercolours, 45 x 57 cm, 1773

The Foundling Museum/ Bridgeman Art Library

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

- The Chapel Looking West

- by John Sanders (1768-1826)

watercolours, 45 x 57 cm, 1773

The Foundling Museum/ Bridgeman Art Library

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

Bluecoat Hospital

The Bluecoat Hospital, in Westminster (now 23 Caxton Street) a charity school for poor children.

It is mentioned in Defoe’s novel Moll Flanders.

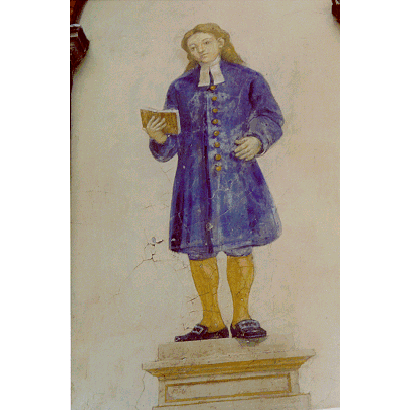

- A “Bluecoat Boy”

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

- Bluecoat Hospital

- [click on the picture to enlarge it]

Photos: Françoise Deconinck-Brossard

Workhouses in London

- A graph and table of the age and gender distribution of the workhouse population for Chelsea, drawn from “Chelsea Workhouse Registers, 1743-66 and 1782-99”

- In Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker, Economic Growth and Social Change in the Eighteenth-Century English Town (TLTP CDRom, Glasgow, 1998)

[click on the picture to enlarge it]

’Bedlam’ (for lunatics)

- See this section: Health and poor relief